Dramatic Editing in GURPS

I’ve been somewhat lax in following the monthly themes proposed by the GURPS blogging community. Let’s see if we can change that! This month’s theme is “Luck”, so let’s see what I can do about it.

What is Dramatic Editing?

If I’m supposed to write about “Luck”, why did I title this article “Dramatic Editing”? That’s the name of a rule in the old White Wolf RPG Adventure!, which was about pulp heroes with special powers in the 1920’s. It used a variant of the Storyteller system, with a “power stat” named Inspiration. In addition to powers specific to their character types, all PCs in Adventure! could pay points of Inspiration to change the narrative around them. In-character, this looked like lucky coincidence, but mechanically it was a conscious decision by the player. The less plausible the change was, the more Inspiration it cost. This rule was called Dramatic Editing.

Hasn’t This Been Done in GURPS Before?

Why, yes! GURPS has several different sets of rules that strongly resemble Adventure!’s Dramatic Editing. Let’s count them.

In the Basic Set alone, we have:

-

The Luck family of advantages, which allow periodic re-rolling certain tests and picking the best result. Higher levels increase the frequency in which this can be done.

-

Super Luck, which allows the player to outright dictate the result of a roll, once per real-time hour.

-

Serendipity, which is very similar to Dramatic Editing but with more GM control and less guidelines as to what’s possible. Each level of the advantage gives one “use” per session.

After that we have GURPS Power-Ups 5: Impulse Buys, which is a whole supplement on the different ways you can spend character points to buy immediate effects. Of particular interest there are the mechanics for Buying Success on p. 16, which at the extreme end can turn a critical failure into a critical success for 5 CP.

Building on that we have the expanded mechanics for Wildcard Skills that debut in GURPS Monster Hunters 1: Champions: for every 12 points spent in a wildcard skill, you also gain a “point” that can be used for Buying Success on rolls of that skill.

These mysterious “points” never had an official name until the Impulse Control article in Pyramid #3/100, which called them Impulse Points and gave us a rule set for purchasing them as advantages.

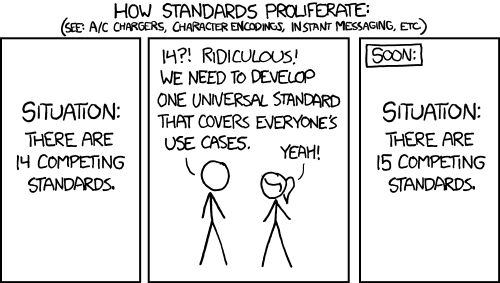

With that many alternatives, why I am even writing this post? Most of various official mechanics don’t really feel unified. If I wanted a game where Dramatic Editing was central, having several of these mechanics in place would be confusing, especially for new players. I also don’t like that the default Impulse Buys rule requires permanent expenditures of character points. The rules associated with Wildcard skills are nifty, but they require bringing Wildcard Skills into the campaign and that isn’t always appropriate.

If I was to use a single official rule set for this, it would be the one from the Pyramid article, but I find even it to be a little too finnicky. You have to pay for your Impulse Point pool and for its refresh rate separately, which means your group can have PCs with different refresh rates. The idea of Villain Points from the article is also pretty good, but making them a fixed disadvantage that also has an individually adjustable refresh rate makes them both predictable and difficult to track.

This can only mean one thing: time to come up with my own system!

Dramatic Editing, GURPS Edition

This system is meant for campaigns where dramatic editing is a major feature. Its use replaces any other traits meant to represent luck, plot protection, or lack thereof. It is inspired several of those traits, by the Dramatic Editing rules in Adventure!, and by similar systems found in a few other games.

Note that these rules use “dramatic” units of time rather than the more traditional GURPS measurements of sessions or periods of real or game time. I prefer to use these units because I often play via forum, where real time and sessions don’t have any meaning:

-

An adventure is a complete story with beginning, middle and end, bookended by significant periods of downtime. In a face-to-face game, it can take several sessions to complete!

-

A scene is a usually series of events taking place in the same location, or something like a single big fight, chase, or significant social encounter. It usually ends when the characters have some time to rest or when the context of their activities changes. A session usually has several scenes, unless the whole session is just one big fight.

The system is built around the following advantage:

Inspiration (15 points/level)

Whether you’re lucky or just that good, you often find things going your way. Each level of this advantage gives you an Inspiration Point (IP for short), which you can spend in the ways described in GURPS Power-Ups 5: Impulse Buys, or in Performing Dramatic Editing, below.

The GM defines how many levels of Inspiration you may buy in the campaign. 3 to 5 should be a typical maximum, depending on how cinematic the campaign is. This advantage is exclusive to PCs, representing the extraordinary luck or “plot armor” posessed by protagonists in heroic fiction. NPC adversaries use a slightly different system. Its use in a campaign implies the use of the rules described below, which apply to all PCs whether they have this advantage or not!

Regaining Inspiration

Inspiration Points can refresh in several different ways:

-

They always fully refresh at the start of every new adventure.

-

In the downtime between scenes of an adventure, you regain 1 or more IP depending on how long the downtime lasted, at the GM’s discretion. A five-minute break while running between fight scenes doesn’t refresh anything, while multiple days of R&R are always worth a full refresh.

-

You gain an IP for particularly good roleplaying during a scene and for heroic actions, at the GM’s discretion. Fortune favors the bold!

-

The GM may give your character 1 or more IP in exchange for inserting negative events into the narrative. Essentially, this allows the GM to buy success or use dramatic editing by giving points to the PCs instead of spending them from a pool.

Points gained through impressive heroics or GM dramatic editing can allow a character to exceed their Inspiration maximum, and even characters without the Inspiration advantage can make use of them! These extra points are lost when the scene ends, so there is extra incentive to use them immediately.

Performing Dramatic Editing

In addition to buying success or improving effect rolls, PCs can use Inspiration to directly alter the narrative around them. While this is a conscious decision by the player, and fueled by the PC’s Inspiration, the PC is not aware of this fact, and perceives this as a stroke of luck or fortunate coincidence. This is usually done to get the character out of danger, or to improve their odds against strong opposition. The more extensive and implausible the change, the more it costs.

Dramatic editing is always initiated by the player, unlike Serendipity, though the GM still may veto or alter edits that violate basic campaign assumptions, exceed the scope the player wants to pay for, utterly break suspension of disbelief, or which simply don’t contribute to making a fun and exciting session. Players should come up with plausible explanations as to why these things happened, and GMs are encouraged to ask for clarification if anything is in doubt.

In any case, using dramatic editing to cause problems for other players is forbidden!

| Change | Cost |

|---|---|

| Minor Change | 2 IPs |

| Major Change | 3 IPs |

| Blatant Continuity Violation | 4 IPs |

| Extension | 1 or 2 IP |

| Additional Complication | -1 IP |

| Offscreen Change | -1 IP |

Below are more detailed descriptions of the possible changes:

-

Minor Change: This change has a minor but not decisive impact on the character’s situation, improving their odds and perhaps giving them some room to breathe. It must be plausible given the current situation, and cannot contradict any established narration. It can do things like bring in plausible friendly NPCs as reinforcements, insert useful objects into the scenery, or give the PC an extra bit of equipment they forgot they brought (like the more specialized Gizmo advantage). The guidelines for standard Serendipity are good here, too.

Examples: There’s a loaded gun in a desk drawer in that penthouse executive office! These sturdy vines will make crossing that jungle chasm easier! Friendly police officers show up when they hear you fighting those mobsters near their station!

-

Major Change: This change has a decisive impact on the character’s situation, turning lost causes into decent fighting chances or perhaps saving the character’s life entirely from certain death. It can stretch plausibility somewhat, but it still cannot contradict established narration and must adhere to the campaign’s base assumptions.

Examples: There’s a parachute in that burning penthouse executive office! Those cops that showed up and arrested everyone know your PCs from way back and are willing to release them with a warning… this time. This idling, unlocked sports car that happens to be here is just what you need to give chase to the bad guys!

-

Blatant Continuity Violation: This change can directly contradict a previously established description, though it still might not violate basic campaign assumptions.

Examples: Turns out the building’s sprinkler system is working after all! The lab had a backup generator the bad guys didn’t know about! This unexplored jungle contains a ruined outpost full of supplies!

-

Extension: Allows a player to “hitch a ride” on an edit just performed by another player, having its effects apply to both PCs. Cost depends on the scope of the original change (minor extensions cost 1 IP, major ones cost 2).

Examples: That vine is a few inches lower than it seemed, allowing both PCs to grab it! There’s water enough for two!

-

Offscreen Change: The edit affects some place other than the one where the current scene focuses on. This means that it won’t be of immediate help, taking anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour of in-game time to have an effect. This reduces the cost of the edit by 1.

Examples: The cops will be here… eventually. That providential supply cache is a ways away.

-

Additional Complication: This change is a mixed blessing - it makes the PC’s life easier in one way, but complicates it in another. Doing this reduces the cost of the change by 1, and it’s equivalent to accepting a bad outcome from the GM in exchange for a point.

Examples: The cops fight the mobsters, but try to arrest you too! The life-saving supply drop fell on top of a nest of snakes!

Dramatic Editing vs. Buying Success

You might notice that even an immediate Blatant Continuity Violation without complications is cheaper than turning a Critical Failure into a Critical Success via the Buying Success rules. The downside of that is that Dramatic Editing is subject to much more GM scrutiny, as described above, whereas a player can normally just spend the IP on buying success and have the effects happen immediately. Generally, anything that could be explained by skill rather than luck should use the Buying Successes rules.

On the other hand, you might also have noticed that the ability to perform an edit equivalent to a standard use of Serendipity per session costs 30 points instead of 15! This is balanced by the fact that characters can recover IP mid-adventure via rest, good roleplaying, heroism, and accepting negative events proposed by the GM, and that this can allow them to temporarily exceed their maximum. And they could always spend those points in Buying Success instead if no good opportunities for “lucky breaks” present themselves.

Adjusting the Rules

The Dramatic Editing rules are purposefully written to a more “fuzzy”, narrative standard than what is usual for GURPS material, and rely a lot on GM and player judgement. GMs who feel that dramatic editing is too powerful as written are free to increase the costs, or come up with more concrete limits on what’s possible. One good way to discourage Blatant Continuity Violations is to set the maximum Inspiration level for the campaign at 3, ensuring that characters can only resort to that most extreme of edits if they surpass their maximum or accept extra complications or delays.

The idea here is that players should use Inspiration early and often. If your players consistently go over their maximums and stay there, you should either encourage them to use those points more often or reduce the amount of awarded points.

Compatibility with Other Systems

If you use Dramatic Editing in a campaign, you should forbid any other Basic Set traits that deal with luck, plot protection or the lack thereof. This includes advantages like Luck and Serendipity, but also disadvantges like Unluckiness, since players get a different sort of reward for allowing bad stuff to happen to their characters. Both forms of Destiny are also forbidden, since recent interpretations of it overlap with the Inspiration advantage.

Using this with “Wilcard points” might be possible, though it makes things harder to keep track of due to characters having several pools of points to spend. Points from Wilcard Skills cannot be used for Dramatic Editing, but can still be used as described in the original rules.

Using this with the Impulse Control rules is relatively straighforward! Simply allow players to spend Impulse Points on Dramatic Editing, using the same cost table and guidelines! This does replace the Serendipity advantage, but all other rules remain as in the article.