The Great Tabletop Hackathon: Shadowrun 1st Edition Design Phase

For this run we’ll be using the original edition of Shadowrun, published in 1989. I started with second edition, but that’s not a problem because I’m equally unfamiliar with both edition’s hacking systems!

The writing and setting and even the rules of these two early editions give me a sort of cozy nostalgic feeling when I read them, but these days I am well aware of all their issues, mechanical and otherwise.

Setting Overview

The setting’s global network is called the Matrix. Hackers are called Deckers because they use cyberdecks, devices the about the size of a full 104-key keyboard that have cable jacks for connecting directly to the decker’s neural interface and to either a computer terminal or a communications line.

Using a cyberdeck to access the Matrix takes you to the full Gibsonian VR Dungeon experience, where you zip through the infinite grid of the Matrix and then crawl through the low-poly simulated environments of a server, treating its security programs as monsters and its data as loot.

Beneath the chrome flash, we’re dealing with classic mainframes from the Eighties. The Matrix isn’t the Internet, it’s the global phone grid. You access your target mainframe by connecting to the phone grid yourself and dialing the number of the mainframe’s modem. There are even rules for making long-distance and international calls. Mainframe numbers are usually unlisted, but can be found with diligent research by deckers or provided by whoever’s hiring them for the run.

A cyberdeck is distinctly different from a mere “computer”, crammed full of specialized electronics that allow it to be used for operating in VR and hacking mainframes. Personal computers don’t do really do much other than letting you store and view data files, and perhaps acting as dumb terminals to mainframes.

Cyberdecks cost a fortune! The one used by the sample starting characters in the book costs more than a sports car. The most expensive one is about twice the price of a fighter jet. And that’s just for the base hardware. If you want your deck to be truly tubular, you’re probably going to spend around twice its base price on software and optional extras. Deckers tend to be highly specialized at character creation because they need to spend most of their points on money and most of their money on a deck - there isn’t any “room” to be anything else.

Mechanics Overview

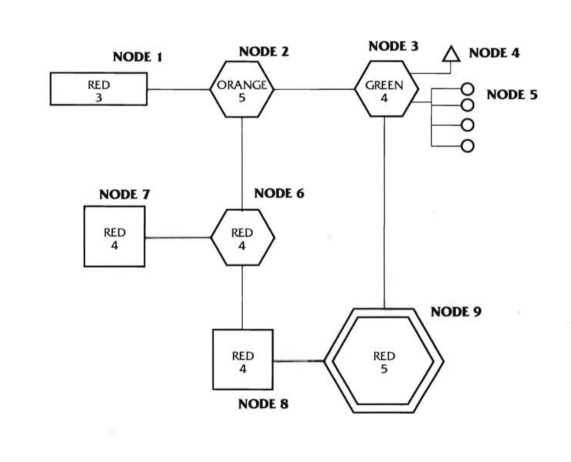

A mainframe is composed of a set of Nodes representing its different parts, connected by Data Lines. The end result is a lot like a dungeon with rooms and corridors.

Each node allows users to perform a different set of System Operations related to its function. Authorized users can do this automatically. Our decker must perform a Computer skill test to beat the node’s Security Rating, a color and number combination that gives you both the difficulty of the roll and how many successes you need. If you fail at performing a system operation, you might trigger an alert.

Deckers can also run Utility Programs, which do things not listed in the system operations menu. There are four program categories, and each has a slightly different procedure that’s some variation of rolling the program rating against the node’s security. Some programs degrade, losing effectiveness each time they’re used. This resets when the decker jacks out. Failing at using a program doesn’t raise an alert, but might trigger IC.

The game is very concerned about how large programs are because there are rules for loading them from disk to RAM and managing your free memory. Not having enough RAM to run all you need at once is the quintessential 80s computing experience after all.

All Computer skill tests and Utility Programs can benefit from the decker’s Hacking Pool, which is equal to the sum of their Computer Skill and Reaction attribute, modified by stuff that increases Reaction. Like other dice pools in this system, it refreshes at the start of every action. You can allocate dice from it to benefit any Computer or Program tests while in the Matrix.

If you want to use a program you don’t have, you can improvise a single-use script version of it with your Hacking Pool. You can only improvise a degrading program once per Matrix run, but if I understand the book correctly you can improvise non-degrading programs multiple times. I’m interpreting the rules to mean that an improvised program must be used in the same action, otherwise there would be little reason to buy any programs.

Most nodes are going to have some IC (Intrusion Countermeasures, “ice”) in them. The mere presence of IC stops deckers from performing system operations or moving past the node, and they must either destroy or fool the IC before they can do these things. Most ice only triggers when it beats you in the opposed test to fool it. If you beat it but fail to beat the node’s base security, they remain inactive and still block your progress. Subsequent attempts are harder, increasing your chances of triggering the ice. Attacking IC directly also triggers it, of course.

White ice is completely passive. It tries to raise an alarm but you can block it with your Hacking Pool. Grey ice additionally tries to trace you or attack your deck. Black Ice attacks the decker directly, and might kill them. There’s a little bestiary of different types within each category.

Matrix turns happen at the same speed as physical combat turns, using the same initiative rules. Both types of turn last around 3 seconds.

Run Parameters

In the Shadowrun 1st Edition version of our run, our decker is going to be remote, and we will assume the team discovered the mainframe’s unlisted phone number during their prep phase. I’m going to take a couple of shortcuts here because those are available to me.

For our decker, we’ll be using the Decker Archetype from the SR1 corebook. She has Computer 6, the Fuchi-4 deck with a decent spread of mods and programs, and a hacking pool of 15. I’m going to cheat a little bit and replace her Deception 4 utility with Sleaze 4, because from what I understood of the system there is no reason to ever take Deception when you can take Sleaze instead. Let’s assume she has one run under her belt and used the payout from that to upgrade her software a bit. Even with Sleaze’s larger size she can still fit all her programs in RAM at once.

For our target system, we’ll be using the one from page 55 of the Mercurial adventure. Here’s a list of the ICE present in the system:

- Node 1: Trace and Dump-4.

- Node 2 Access-6.

- Node 3: Barrier-3.

- Node 4: no ICE.

- Node 5: no ICE.

- Node 6: Killer-4.

- Node 7: Access-5

- Node 8: Black Ice-5.

- Node 9: Trace and Burn-6, Black Ice-4.

Node 4 will be connected to our security camera, Node 5 to the alarm and door. Node 8 will contain the evidence we seek, and the CPU at Node 9 is where we can drain their accounts because that’s how it is in the original adventure. The other data store at Node 7 has nothing of value to our runners.