Posts

-

Let's Read the 4e Monster Manual 2: Firbolg

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast This article is part of a series! Click here to see the other entries.

Firbolgs are inspired by Celtic myth, and I’m sure they must have appeared in earlier editions in some form. I think their 4e presentation in this book is new, though.

The Lore

Firbolgs are giants (not Giants) native to the Feywild. Their culture values independence and courage, and their religion is a variant of the Maiden-Mother-Crone triumvirate. This variant has a different goddess in each role: Sehanine is the Maiden, Melora is the Mother, and the Raven Queen is the Crone. This generally results in a religion that’s themed around the night, the moon, autumn and winter, instead of the more balanced “classical” version.

Firbolgs live in and protect the deep wilderness of the Feywild, building their settlements on precarious peaks, floating earth motes, and other such hazardous heights. Leadership positions are occupied by their mightiest warriors and their moon seers (priestesses), both of whom wear masks or helmets styled after one of their deities. They place great value on clan and family ties.

Back when I discussed the Hounds of the Wild Hunt, I speculated that the hunters would be high-powered eladrin. Well, I was wrong! Turns out the Wild Hunt is a Firbolg tradition.

You see, while firbolgs are fond of treasure, they place even greater value in oaths and promises. And when someone breaks an oath made to the firbolgs, they convene a Wild Hunt to track and punish the infractor. Even people who didn’t betray the firbolgs directly still have reason to fear them, as there’s a ritual that allows someone to sic a Wild Hunt on an oathbreaker. And I imagine they might also ride out to fulfill sacred missions revealed in the moon seers’ visions.

Wild Hunts vary in size and composition, and might include allied sapients whose goals and temperament are close to those of the firbolgs themselves. The mightiest and scariest hunts are led by firbolgs with the oficial title of Master of the Wild Hunt, who usually act as community leaders while not fulfilling that role.

PCs might find themselves fighting firbolgs when they stumble on their territory, since a firbolg attack will likely be the first sign that they did it. They could also find themselves on the path of a Wild Hunt, or even as their main target if they manage to piss off someone who can convince the Hunt the PCs are oathbreakers.

Still, it’s possible to negotiate with firbolgs and even approach them peacefully. The Wild Hunt is harder to parley with, but it’s still not impossible unless the PCs really are oathbreakers. Of course, should their interests align, the PCs might find themselves riding alongside the hunters.

The Numbers

Firbolgs are Large Fey Humanoids, and all the ones we see here are Unaligned. They all have low-light vision and a natural ground speed of 8. They also have Regeneration 5 (10 at Epic tier), which can be shut down for a turn by necrotic damage.

They also have a +2 bonus on saves against charm effects, and the immobilized, slowed and restrained conditions. For elite firbolgs, this stacks with the +2 on all saves elites get.

Their signature power is Moonfire (Ranged 10 vs. Will; minor action; recharge 4+), which prevents the target from benefitting from cover or concealment for a turn. It also has additional effects that vary per stat block, but all generally make the target more vulnerable to that firbolg’s attacks. All of their other powers come from martial or magic training, and their magic has the same themes as their religion.

Firbolg Hounder

Hounders are members of firbolg hunting parties whose job is to attack and drive prey into a position that makes them vulnerable to the other hunters. They wear scale and wield axes and shields. They’re Level 11 Soldiers with 113 HP.

Their basic attack is a Reach 2 Battleaxe, and they can use it in a Hounding Strike maneuver that has the same basic stats and also slides the target 2 squares on a hit. Drive Prey is an even more powerful version of that, doing more damage and allowing a secondary attack vs. Will. If that hits, the target must move or shift away from the hounder with its first action on its next turn, or become dazed until the end of that turn. This ability recharges when the hounder is first bloodied.

At range, the hounder can throw Handaxes, which do light physical damage and knock the target prone. Their Moonfire power also marks the target for a turn. Finally, the Hunter’s Leap passive trait makes them immune to opportunity attacks while jumping. They use the standard jumping rules for that.

So it looks like these firbolgs will use Hounding Strike and Drive Prey to slide enemies into a vulnerable position, and then either stay away and throw handaxes, or move into melee to try and keep the enemy pinned in place while the other hunters do their jobs.

Firbolg Hunter

These are the people the hounder (above) works with. They’re level 12 Skirmishers with 123 HP, wear light armor and bring spears and javelins to bear agains their prey.

All of their powers enhance their weapon attacks. Crippling Strike (recharges when first bloodied) adds extra damage to an attack and makes it immobilize the target (save ends) with a Slow after-effect. Mobile Attack allows them to move 8 squares and make a basic attack without provoking opportunity attacks from the target, or from making ranged attacks. Their Moonfire also makes their weapon attacks do +1d6 damage to the affected target for a turn.

And finally, they also have Hunter’s Leap. It’s really hard to run from them, particularly when there hounders pinning you down.

Firbolg Moon Seer

Moon Seers are those priestesses I talked about. They’re Level 14 Controllers with 141 HP. They wear masks and light armor, and fight with moon- and fate-themed magic.

A seer’s basic melee attack is a Moon Mace that targets Reflex, deals Radiant damage, and blinds the target until the start of its next turn. Their Moonfire has the additional effect of making targets grand combat advantage to the seer for a turn. After hitting someone with Moonfire, the seer can use Moonstrike (vs. Will) to deal psychic damage to that victim and dominate them until the end of the seer’s next turn.

There’s two other spells Spirit Hounds and Ban of the Raven.

Spirit Hounds is a blast that targets Reflex and only affects enemies. It deals psychic damage, slows, and prevents the target from teleporting (save ends), which is handy when hunting down eladrin or other fey.

Ban of the Raven is the big gun, an encounter power that’s a Ranged 10 vs. Fortitude attack. It deals heavy necrotic damage and worsens critical hits! The affected victim takes critical hits on a natural 18-20 instead of only a 20, and each such hit deals an extra 10 necrotic damage on top of whatever it would normally deal. Once the victim saves against that there’s still a weaker aftereffect that makes the victim suffer crits on a 19-20.

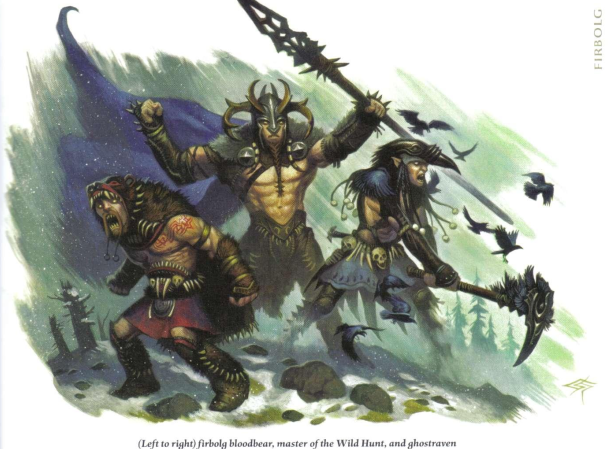

Firbolg Bloodbear

Bloodbears mix in a bit of viking into their Celtic trappings, being able to turn into bear hybrids. They’re Level 15 Elite Brutes with 240 HP.

They fight unarmed, and start out in firbolg form. Once bloodied, they assume Bloodbear Form, recover all of their HP, and double their regeneration. This also upgrades all of their attacks. This transformation lasts until they’re bloodied again, and then it reverts. So in effect they have 360 HP, and will become bears for the middle third of that health bar.

In firbolg form, they fight unarmed with slams, and they can slam twice with Double Attack. If they hit both attacks, they can also try to grab the target. Bloodbear Maul allows them to automatically deal heavy physical damage against the grabbed victim. They have Moonfire, but it’s only the basic version.

In bloodbear form their slams turn into claw attacks that gain increased damage, they gain a bite that does even more damage and deals ongoing damage if the target is granting AC, and Bloodbear Maul also allows them to make a free bite attack against the grabbed target.

Firbolg Ghostraven

These are Raven Queen themed assassins. They fight with heavy war picks, which are not the kind of weapon you’d expect an assassin to use. They can assume the form of a ghostly raven, which allows them to better hide in shadows and ambush their intended victims.

Ghostravens are Level 16 Elite Lurkers with 238 HP. Their picks are High-Crit weapons, and they can attack twice with them. If both attacks hit the victim is blinded (save ends). Assuming Ghostraven Form is a minor action that makes them intangible, gives them a fly speed of 8, and gives them concealment while in dim light or darkness. When a ghostraven attacks someone who can’t see it, it deals increased damage.

Firbolg Master of The Wild Hunt

What it says on the tin. These hunt masters usually serve as leaders of firbolg communities when they’re not heading a Wild Hunt.

Hunt Masters are Level 22 Elite Skirmishers with 404 HP. They wear the classic stag helmet and fight with a Spear of the Hunt that can make both melee and ranged attacks (it returns when thrown). Being elites, they can attack twice per action.

Their Moonfire also marks and makes the target grant combat advantage until the end of the master’s next turn. They deal increased damage to targets affected by Moonfire (from any firbolg, not just their own).

Their special attack is a Mortal Strike, which allows them to make a basic attack against a bloodied enemy that’s an automatic critical and deals 6d6 additional damage. If this reduces the target to 0 HP, it gives an extra action point to the huntmaster. Action Points, as a reminder, can be spent to give their owner a whole extra standard action on their turn. All elites start out with one, and the hunt master is one of the few who can gain more during a fight.

Sample Encounters and Final Impressions

We get two encounters:

The first is Level 13, a moon seer, a hunter and two hounders plus 2 centaur hunters. This is either a “lesser” Wild Hunt or just a normal hunting party/patrol. It hints that there’s likely a joint Centaur/Firbolg culture out there somehwer.

The second is a proper scary Wild Hunt: the Master of the Wild Hunt along with two Wild Hunt hounds, a bloodbear, and 2 ghostravens. It’s level 22, which means relatively few things in the setting can really stand up to it.

I like firbolgs more than I though I would! There’s plenty of information on them here, and it does plenty to differentiate them from the more standard giants.

One thing I found a bit awkward are the bits of text in the book that say they value “the middle path between good and evil”. This is derived from one of Sehanine’s commandments, which is equally awkward. What does this mean? Are they supposed to feed a puppy one day and kick it on the next to keep things balanced? A more charitable interpretation might be that they’re not any more inclined to trust people who claim to be champions of good than they are anyone else, and try to stay out of those particular cosmic struggles.

-

Let's Read the 4e Monster Manual 2: Fey Lingerer

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast This article is part of a series! Click here to see the other entries.

I think it’s fair to say that eladrins can be overachievers. Their societies produce a lot of gallant knights and powerful spellcasters, who go on to accumulate glory and renown to their name. They’ll be the first to say the world is a better place due to their efforts.

Sometimes, though, things go wrong. A knight perishes with a quest unfulfilled, or a mage dies just before making that one crucial breakthrough that would get him tenure at Lórien Polytechnic. Whether from violence, accident or natural causes, such deaths are incredibly frustrating for the eladrin in question, so they simply refuse to go. The entity that results from this is known as a Fey Lingerer.

Fey lingerers resemble the people they were in life, but the book describes then as “withdrawn from elven grace”. In other words, they look clearly dead, their formerly shiny countenances now decomposed or dessicated. They’re also quite cruel and anti-social, their personalities now dominated by the frustration and anger that kept them from passing on.

Lingerers generally try to accomplish whatever it is they were trying to do when they died, and can linger on even after that, looking for ways to gain the glory and fame they feel were due to them while they lived. They might employ other undead in this, and sometimes they also gather living eladrin followers who are willing to help their fallen heroes.

When a fey lingerer is destroyed in combat, its spirit emerges angrier than ever. This vestige knows it can never complete its objectives now that its body has been destroyed, and becomes obsessed with taking revenge on those responsible.

The Numbers

Fey lingerers are corporeal undead, and since they used to be overachieving eladrin luminaries, they’re usually mid-to-late Paragon-tier. As is standard for undead, they have Darkvision plus some level of Necrotic resistance and Radiant Vulnerability.

Lingerers retain the eladrin Fey Step power, and add an aura of Spiraling Despair (radius 3) which inflicts a -2 penalty to attacks and saves to enemies caught inside. They also have an extra bonus on saves against charm effects.

They’re Elite monsters, but this is implemented in a novel and very interesting way. Normally an Elite would have double HP, but Fey Lingerers have the normal amount. However, when they hit 0 HP they become Vestiges, incorporeal undead with their own stat blocks. They start in the same position as the original lingerer, and act on the same initiative order, but are otherwise treated as if they had just entered the fight: full HP, all abilities unused.

Vestiges aren’t worth any additional XP when fought as part of a lingerer fight since the lingerer’s XP total accounts for them. You can design encounters with vestiges directly, though, and in that case they’re worth XP as normal for a regular monster of their level.

Lingerer Knight

These knights usually died when trying to fulfill an important mission or quest, and are driven to complete it. They might have been honorable sorts before their deaths, but now they’re just desperate. Bearing the same weapons they did in life, they can infuse their strikes with necrotic energy and force enemies to experience their rather unhealthy mental state.

Lingerer Knights are Level 16 Elite Soldiers with 152 HP. They have all standard lingerer traits and a speed of 6. Their necrotic resistance is 10, and their radiant vulnerability 5. The one in the book fights with a Longsword that also inflicts ongoing necrotic damage (save ends). Double Attack allows it to perform two sword attacks in a single action.

They can also perform a spell called Spirit Sword Circle (recharge 5+), a Close Burst 1 vs. Reflex that does slightly less damage than a double attack and also inflicts ongoing necrotic damage (save ends).

That unhealthy mental state manifests as two different powers: Desperate Challenge (Ranged 10; Encounter) allows the knight to mark a target until the end of the fight or until the knight discorporates, whichever comes first. Marked targets take some automatic necrotic damage when they make an attack that doesn’t target the knight. Spiritual Despondence triggers when the knight is first bloodied and deals automatic necrotic damage in a Close Burst 3.

Fey-Knight Vestige

A destroyed lingerer knight becomes one of these. It’s a Level 16 Lurker with 75 HP. It has all standard lingerer traits, a ground speed of 6, and a fly speed of 6. Its resistances and vulnerabilities increase by 5 each, and it’s also insubstantial.

The vestige fights with a Ghostsword that targets Fortitude instead of AC, does necrotic damage, and makes the target grant combat advantage to the vestige (save ends). This means it can do its “Lurker thing” while staying in the front lines, which is a bit unusual but matches the “knight” flavor. Desperate Dash (move; recharge 5+) allows it to shift 6 squares and possibly escape being surrounded.

Lingerer Fell Incanter

Fell Incanters hang around for more open-ended reasons than knights, and are usually obsessed with obtaining more arcane knowledge and power in order to Show Them All. Their magic is tinted with their hatred, so all of it does necrotic damage. So they’re kind of Lich-Lite.

Fell Incanters are Level 18 Elite Artillery with 130 HP and all standard lingerer traits. They’re armed with a quarterstaff that also inflicts ongoing necrotic damage (save ends).

At range they can fire Soul Bolts (ranged 10 vs. Fortitude) that deal necrotic damage and immobilize (save ends). Double Attack allows them to shoot two of these in one action. After they’re bloodied, they can also use a Soul Blast (close blast 3 vs. Fortitude; recharge 5+) that does necrotic damage and weakens until the end of the incanter’s next turn.

Fey-Incanter Vestige

When a fell incanter is destroyed, it becomes one of these. It’s a Level 18 Lurker with 91 HP. Its resistances and vulnerabilities are increased by 5 each, it gains a fly speed, and becomes insubstantial.

Incanter vestiges have no melee attacks. Their basic attack is a Ray of Humility (Ranged 5 vs. Will) doing both immediate and ongoing necrotic damage. It also inflicts 5e disadvantage (roll 2d20 and take the lowest die) on the victim’s saves, with a successful save ending both this and the ongoing damage.

There’s also Ray of Spring’s Rejection (ranged 5 vs. Will; recharge 5+), which does more damage and makes the target grant combat advantage to the vestige (save ends). And, like the knight vestige, this one deals increased damage to people granting CA to it.

This results in an enemy that’s a bit similar to the knight vestige but with a ranged focus. It’s also a lot harder to save against its CA-granting effect.

Sample Encounters and Final Impressions

The sample encounter is Level 18: two lingerer knights, 1 fell incanter, and a living bralani of autumn winds who is probably one of the incanter’s fan-elves.

I think fey lingerers are really interesting! Though I described them as “Lich Lite”, I actually think they’re a bit more flavorful than standard liches, what with the whole “become a vengeful ghost” mechanic. I always felt D&D 4 could have done a lot more with such multi-stage enemies.

-

Let's Read the 4e Monster Manual 2: Fell Taint

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast This article is part of a series! Click here to see the other entries.

I think fell taints are new to 4e - at least, this book is where I first heard of them. If they showed up in previous editions, it was probably in 3e.

The Lore

I confess the name made me think of something you might find staining an ogre’s underwear, but that’s not the case. Fell Taints are small predators from the Far Realm, where they occupy a niche more or less equivalent to that of our foxes. However, they’re quite a bit more dangerous when they cross into the world, which they can do rather easily in places where the border between it and the Far Realm is even a little bit thinner than usual.

Their presence acts as a beacon for more powerful and dangerous Far Realm denizens, and slowly erodes the barrier between dimensions. So if you have fell taints in a place, you’ll soon get bigger horrors from beyond popping up.

The taints themselves are also dangerous on their own, since they hunt by destroying the mind of their intended prey with their psychic powers. This is not exactly something most mortal creatures have a strong defense against.

One of the bizarre things about Fell Taints is that they’re only half real. The other half is formed by the minds of those who see them.

The Numbers

Fell Taints are Baby’s First Elder Things, with levels in the early-to-mid Heroic tier. If you’re starting an aberrant-themed campaign from Level 1, they’re going to be the first genuine Far Realm denizens your party meets.

Fell Taints can fly quite well with a speed of 6 and hover capability, or crawl along the ground at speed 1 if they must. They’re insubstantial due to that half-real thing, but vulnerable to psychic damage. The touch of their tendrils causes psychic damage, and they usually have mind-affecting special attacks as well. They’re all Aberrant Magical Beasts, and most are Small.

An ability they all share is Fell Taint Feeding: when they manage to get a victim helpless or unconscious, they can begin to feed. This causes them to lose their fly speed and become substantial until the end of their next turn, but allows them to perform a coup de grace against the victim. If this kills the victim, the fell taint immediately recovers all of its hit points. Yeah, they’ll absolutely attempt to kill any PC that drops to 0 HP during the fight.

Fell Taint Lasher

Lashers are Level 1 Soldiers with 20 HP and all standard traits outlined above. Their special attack is Tendrils of Stasis, which does a bit less damage than the basic tendril slap and immobilizes the target for a turn. When making an opportunity attack, they can shift as a free action.

Fell Taint Pulsar

Pulsars are Level 1 Artillery with 18 HP and all common traits. Their special attacks are a Range 20 tendril pulse that does psychic damage, and a Ranged 10 tendril flurry that makes a slightly weaker attack against up to three targets.

Fell Taint Tought Eater

These are Level 2 Controllers with 26 HP and all standard traits. They have two special attacks.

Spirit Haze is a Range 10 attack that does psychic damage and dazes for a turn. Tought Fog (recharge 5+) is a Close Burst 5 that only targets enemies, does no damage, and slows. This worsens to immobilization after the first failed save.

Fell Taint Warp Wender

This Level 4 Controller is Medium, and has 38 HP. Its single special attack is Psychic Transposition, which does light psychic damage, dazes (save ends) and makes the taint and the victim teleport to exchange places.

Sample Encounters and Final Impressions

The sample encounters are mostly mixed fell taint groups, because they rarely work with anyone else. Still, they might be coincidentally found alongside undead or oozes, creatures they find unapettizing. I imagine some cultists and such might also know how to bind them.

As a party’s first contact with the Far Realm, I think these creatures are quite nifty. They look weird enough to unsettle, and each has a single distinctive mechanical trick.

-

Let's Read the 4e Monster Manual 2: Elemental

This article is part of a series! Click here to see the other entries.

Technically, any creature with the “elemental” origin is an elemental, but as we saw in the Elemental entry from the first monster manual the name is also used for a particularly wild subset of that plane’s denizens.

As you can see in that earlier post, Elementals proper are some of the “basest” life forms of the Elemental Chaos, with bodies that share a lot more with their constituent elements than with any sort of living organism. Unlike demons they’re not actively malicious, but they’re mercurial and easy to provoke into a rampage.

As magical beasts, they’re technically sapient, but their intellects tend to be rather limited. These creatures are also often bound by elementally-inclined ritual casters such as mortal wizards, efreets, and others.

The MM2 presents us with more elementals ranging from the mid-Heroic to the early Epic tier.

Chillfire Destroyer

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast A Large humanoid made of ice wrapped around a fiery core, which means it has zero chill. It’s a Level 14 Brute with 173 HP, lumbering about at Speed 5. It has 10 resistance to cold and fire, and is immune to disease and poison. Its fists do a mix of fire and cold damage, and it can also move its speed and trample anyone it comes into contact with during this movement.

As this elemental gets damaged, its shell begins to crack. Once it’s bloodied, its Leaking Firecore acts as an aura (radius 2) that deals fire damage to anyone caught inside. Once it reaches 0 HP, a Firecore Breach causes it to explode! This explosion is a Close Burst 3 vs. Reflex, dealing heavy fire damage.

Dust Devil

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast A being or air and earth, this capricious living whirlwind has a tendency to sandblast anyone who makes it angry. It’s Small, and a Level 3 Skirmisher with 47 HP and a ground speed of 8. No, they can’t fly. It’s immune to disease and poison, and it suffers a -2 penalty to all of its defenses if slowed or immobilized.

Its basic attack is Grasping Winds, which targets Reflex, does some physical damage and slides the target 3 squares. Gale Blast allows it to shift 5 squares by moving really fast, and try to knock anyone in the way prone (attack vs. Fortitude).

Once per encounter it can do that sandblasting trick with Stinging Sands (close burst 3 vs. Fortitude), which does heavy damage and blinds for a turn.

Flamespiker

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast These are a triple combination of air, earth, and fire, taking the form of a Medium stony humanoid who can use high-pressure air to fire red-hot spikes from its fiery core. They’re more like people than wildlife, and often end up hired as front-line muscle by other sapient elementals.

Flamespikers are level 5 soldiers with 66 HP and a ground speed of 7. Their immunities include disease, poison, and petrification, and they also have 10 fire resistance.

The flamespiker fights with its Reach 2 Stonespikes in melee, and can also fire them at out to range 10 as Spikebolts. Both attacks do physical damage, and the melee one also makes the target vulnerable to fire damage until the end of the spiker’s next turn. So it pairs really well with fire elementals.

If an enemy within reach shifts, the stonespiker can react with a Thunderfire Thrust (recharge 5+), which is a basic melee attack with an extra follow-up against Fortitude that does 5 thunder damage and stuns (save ends). This makes slipping past them a difficult proposition.

Geonid

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast This Large creature has more of a metabolism than most elementals, and needs to hunt. A stony oyster-like creature, the geonid is extremely hard to tell apart from a boulder when its shell is closed. When it reveals itself, we can see that it’s yet another tentacular ambush predator that lives in the shallow Underdark.

They were initially created to guard the secret pathways of the world, and the secret caches of weapons, dormant war-beasts, and treasure hidden there by the forces of the primordials. Some of those caches are still out there, as are their guardians.

Geonids are Level 6 Lurkers with 56 HP. They’re immune to disease, petrification and poison, and cal roll around at speed 4. With its shell closed, potential victims must pass a DC 28 Perception check to realize it’s not a harmless boulder. At level 6, this is hard even for the party’s “radar”.

Once the geonid strikes, it fights with tentacle slaps that do standard physical damage. It can also use a capturing grab that consists of two weaker tentacle attacks. If both hit, it grabs the target (escape DC 17).

Once it’s grabbed someone, the geonid will close itself with Shell Slam, which does a lot of things at once. It slides a grabbed victim to the geonid’s space, and it tries to knock everyone in a close burst 2 prone (vs. Fortitude).

While the shell is closed, the geonid has a ground speed of 0 and a +5 to all of its defenses, and it can’t target anyone other than the grabbed victim it pulled inside its shell. The victim can also only target the geonid, but on the bright side it won’t have to contend with the defense bonus. If the victim escapes, it gets spit out and appears adjacent to the geonid, who can open its shell with a minor action.

Mudlasher

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast Another sapient elemental predator, mudlashers are made of well, mud. They slam and drown their victims, and then sit atop the corpse as a puddle to slowly digest it. They’re Medium Level 4 Brutes with 63 HP.

Their basic Slams do physical damage, and once per fight they can upgrade that to a Drowning Slam that targets Fortitude and adds an ongoing damage follow-up (save ends).

They can also fling mud balls at range (vs. Reflex), which do no damage but slow their targets. If a target is already slowed, it’s immobilized instead. This is good because the mudlasher gets a +2 to attacks against slowed or immobilized targets. A save will end either condition.

Rockfist Smasher

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast The name says it all: they’re humanoid rocks that like to smash with their fists. Smashers don’t need to eat, so they do that for fun. People who build elemental themed dungeons like to gather a bunch of these and lock them in chambers and at the bottom of pits as living traps.

These hooligans are Large, Level 10 Brutes with 125 HP, the standard suite of earth-creature immunities, and a speed of 5. Their Granite Punches do good damage and knock bloodied targets prone.

When a smasher gets bloodied itself, its Internal Avalanche triggers and begins accumulating kinetic energy. This gives the smasher 20 temporary HP. If it still has any temp HP at the start of its next turn, it gains an action point that must be used in that turn.

Shardstorm Vortex

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast These are living blizzards made of stone instead of ice. Despite this impressive description, they’re just Medium in size and are the scavengers of the Elemental Chaos. Shardstorms follow in the wake of more impressive beings and feed on what remains of their battles. In battle they work like slightly stronger dust devils.

They’re level 7 skirmishers with 80 HP. Their ground speed is 0, but they fly at speed 8 with hover capability and project a Sandblast aura (radius 1) that inflicts a -2 to all defenses of anyone caught inside.

Their basic attack is a Abrasive Slam that targets Fortitude and does physical damage. They can also perform Whirling Blasts (recharge 5+) that allow them to shift 4 squares and an attack at the end. This does heavy damage and pushes 1 square on a hit. It does half damage on a miss.

We also get two variant stat blocks for them as minions at levels 13 and 23. They still have the aura and the basic attack, but instead of the Blast they get a Vortex Step, an at-will 4-square shift with no built-in attack.

Stormstone Fury

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast This is a Medium stone humanoid infused with the power of a storm. It can throw explosive stones, cause shrapnel to fly outward from its body, and meld into the ground for a quick escape. When fighting as part of a team they don’t really care about catching allies in their blasts, so if you find yourself on the same side as one of these, bring some thunder protection.

Furies are Level 14 Artillery with 113 HP and Speed 6. They have the usual immunity suite, and 10 thunder resistance. Its Grinding Stones melee basic attack is terrible, but its Hurtling Thunderstones have Range 20 and do half damage on a miss. Hit or miss, they also cause a follow-up explosion (burst 2 vs. Fortitude) that does thunder damage.

Shrapnel Burst is their “keep away from me” power, sending shrapnel that pushes 2 squares and does physical and thunder damage in a close burst 2 (vs. AC). If that fails, Meld to Ground removes them from the map for a turn, after which they reappear up to 10 squares away.

Tempest Wisp

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast This gaseous creature is a bit smarter than your average elemental, and actively seeks to either ally with or coerce other creatures to form groups that cooperate against threats. It uses its wind powers to push enemies around the battlefield, and hides behind its allies to avoid damage.

Tempest Wisps are Level 13 Controllers with 134 HP. They’re immune to disease and poison, and are insubstantial while not bloodied (i.e, while at over 50% HP). They have a flight speed of 7 with hover capability.

Their basic attack is an Air Slash (vs. Reflex) that does physical damage, and they can attack at range with Whistling Wind (ranged 10 vs. Reflex) for about the same damage and a 1-square slide.

Their limited special attack is hilarious! Named Tumbling Updraft (ranged 10 vs. Fortitude; recharge 5+), it does no immediate damage but instead lifts the target 20 feet up on a hit and restrains them (save ends). Each failed save causes the victim to be tossed up another 20 feet. On a successful save, the victim falls! That’s a minimum of 2d10 fall damage, plus another 2d10 for every failed save. It’s all subject to the standard rules for falls, though, so you might be able to reduce or avoid this damage in the usual ways.

Windfiend Fury

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast Yet another Angry Tornado, this one more purely “stormy” than the others. These Large beings like to hang around elemental storms, and so tend to get swept away into other planes. Sometimes archons will capture them and bind them to their flying ships as a power source and as a means to travel to other planes. You can also say these are the beings trapped at the core of those Eberron flying ships.

These are Level 12 Controllers with 123 HP and a flight speed of 8. Aside from the usual immunities to disease and poison they have 15 resistance to lightning and thunder.

They attack in melee with Flying Debris, and toss Lightning Strikes at range that do lightning damage and daze for a turn. Their “keep away!” power is a Storm Burst that does thunder damage and teleports them to just outside the area of effect.

Windstriker

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast Our final Angry Tornado is Medium, and a Level 9 Lurker with 56 HP. They have the usual immunities and full-time insubstantiality, along with a flight speed of 8. It attacks unpredictably, though apparently not to feed.

All of their attacks do “cold and thunder” damage. They’re probably going to open up with Searching Wind (ranged 10 vs. Will), which knocks prone on a hit and marks the target as the windstriker’s quarry as an effect. Then they’ll follow that up with Lethal Windstrike (melee 2 vs. AC), which hits hard but only works against the quarry. Their basic Windstrike is a lot weaker, so it’s for emergencies only.

If the windstriker takes damage, it activates Shifting Wind as a reaction, which gives it the ability to ignore opportunity attacks and pass through enemy spaces during its next turn. So it’s going to be flitting back and forth to alternate marking someone as a quarry and attempting to assassinate them.

Encounters and Final Impressions

There’s a whole bunch of sample encounters here, but they’re all easily to described: assorted elementals of similar level, occasionally with someone who might be the spellcaster binding them, like a tiefling heretic or a beholder.

I like the lore of elementals in 4e on principle, and we have lots of mechanically varied stat blocks here… but there’s so many of them that they all kinda started blurring together by the end. I almost wish we had gotten an elemental “plug-in” module for the 4e monster design system rather than this long list full of angry rock giants and angry living tornadoes.

-

Let's Read the 4e Monster Manual 2: Eladrin

Copyright 2009 Wizards of the Coast This article is part of a series! Click here to see the other entries.

We already discussed the lore of the Eladrin over here, along with how they differ from your standard elves and from the celestials of 3e. I recommend reading that post again for those basics.

The Monster Manual 2 contains three more eladrin stat blocks, along with a bit of additional lore on their society. I find it very funny that two of them correspond to very popular elfy classes of editions past, debuting in 4e in the form of monster entries. It would be some time before playable versions of them were published, which I imagine must have made their fans quite anxious.

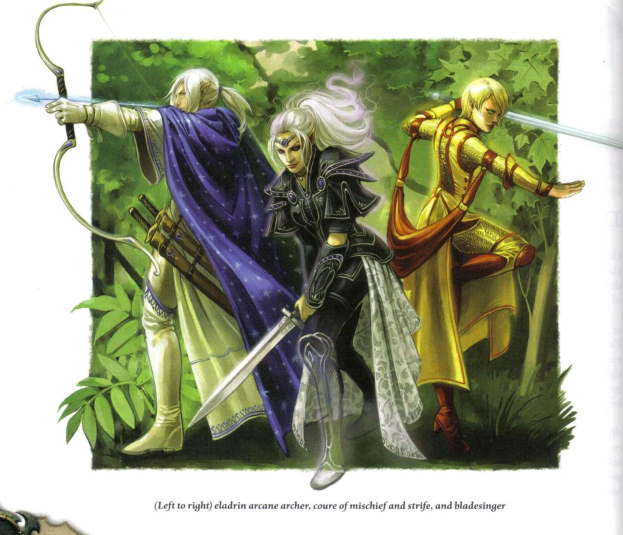

Eladrin Arcane Archer

Arcane Archers are more than just wizards who can shoot a bow. They practice an art that’s seamless fusion of the two disciplines, and whose secrets are jealously kept by certain eladrin societies. The Bow Mage minions we saw in the MM1 are likely to practice the same style. This entry would represent a more advanced, experienced, or narratively important practitioner.

I don’t think we ever explicitly got an Arcane Archer class in 4e. The Seeker tries to implement the concept using primal magic but ends up not being very effective. I think there’s also a way to build a Bard specializing in magic ranged attacks with a bow.

The Numbers

Arcane Archers are Level 5 Artillery with 51 HP. Their speed is 6 and they have low-light vision, along with the standard Fey Step power all eladrin get.

In a fight, they stay at range and repeatedly fire Scorching Arrows from their bows. This ability is kinda like a better version of the PC Ranger’s Twin Strike, allowing them to make two attacks that target the lower of AC and Reflex. The arrows have the same range as mundane ones, and individually deal a low-ish mix of physical and fire damage. This adds up, though: an arcane archer that consistently hits with both attacks punches a fair bit above its weight class.

They can also fire an arrow that explodes into an Eldricht Burst (area burst 1 within 20 vs Fortitude; recharge 4+). This deals force damage and knocks enemies prone on a hit.

Eladrin Bladesingers

Ah, bladesingers. I first heard of them in 2e and I can’t remember a more controversial class from that edition, at least here in the Brazilian fan community. People either really loved them or really hated them. While I was eventually convinced that their highly cinematic combat style was cool, I never liked that they were an elf-only option.

Anyway, 4e bladesingers are eladrin practitioners of an ancient martial art that joins swordplay and magic. The resulting style resembles something a Jedi knight or wuxia hero might use, employing lots of empowered sword strikes and magic-assisted acrobatic maneuvers. Their code of conduct has elegance as an important principle, so they put real effort into making their combat techniques both graceful and effective.

The same code also compels them to behave honorably, so they tend to treat opponents with respect and despise those who slaughter the weak and defenseless. Despite this, there are many possible reasons for even a party of good-aligned PCs to come into conflict with bladesingers: they might have offended the eladrin’s liege, or a given group of bladesingers might have fallen to the Dark Side of the Force.

You can get pretty close to a playable bladesinger by playing a Swordmage, and apparently there was also a “bladesinger” class published late in the edition. More obliquely, a Blade Pact Fey Warlock could also fit the concept.

The Numbers

The MM2 bladesinger is a Level 11 Skirmisher with 114 HP. They have a very nice ground speed of 8, in addition to the low-light vision and Fey Step power all eladrin get.

They wear mail and wield a longsword, both of which are probably magical or at least very high quality. Their basic attack is a Brilliant Blade strike, which deals radiant damage and gives the target a -3 penalty to attack the bladesinger during the target’s next turn.

Dance of Brilliance is an at-will combination that allows them to make an attack dealing light radiant damage, shift 3 squares, and make a basic Brilliant Blade attack against another target.

They have two encounter powers. Crippling Strike targets Fortitude and deals no damage, but is guaranteed to slow the target even on a miss. On a hit it also weakens them. In both cases the conditions are “save ends”.

Wyvern Strike is much better, allowing the bladesinger to fly 8 squares without provoking opportunity attacks and perform a strike at any poing along the movement. This targets Fortitude, deals light physical damage, and 10 ongoing poison damage (save ends).

Finally there’s Combat Shift. This allows them to shift 1 square as a minor action, ending up adjacent to an enemy against which they have combat advantage.

Coure of Mischief and Strife

Time for more surreal fey nobility! Like “bralani” and “ghaele”, “coure” is a noble title whose meaning can be a little confusing to mortals. One of the reasons for this is that while most eladrin societies use the same names for the titles, the actual rank they confer, and the amount of influence attached to them, varies from culture to culture. So in this city state ghaeles might be the rulers, but on that kingdom over there they’re just minor provincial nobles and it’s the coures who call the shots. Attaining a noble title is rarely a matter of inheritance - there’s a lot of mystery and mystycism involved.

Whatever their rank, though, these titles always have some natural phenomenon or abstract concept attached to them, like “autumn winds”, “winter”, or “mischef and strife” in this entry. The noble in question will always have powers relating to this area of influence.

So yeah, a coure of mischief and strife is a pointy-eared Loki.

The Numbers

This coure is a Level 17 Lurker with 129 HP. It has the usual low-light vision and Fey Step ability, which in this case is completely redundant because the coure also has a teleport speed of 6 to complement its ground speed of 6. It wears leathers and fights with a rapier.

The coure can become invisible at will as a standard action, and this lasts until it takes damage or misses with an attack. If it attacks and hits, it stays invisible! If for some reason the eladrin doesn’t already starts the fight invisible, this is going to be its very first action.

Once the invisible trickster is close to the party, Winds of Luck’s Mischief is a good fight opener: a Close Burst 3 vs. Will that does no damage, but makes everyone it affects miss all attacks whose attack rolls were odd. This is a “save ends” condition, so it might stick around for a while! Good luck trying to damage an invisible enemy when half of your blows veer off course.

While invisible the coure can also use Spark of Strife, a Ranged 10 attack vs. Will that deals psychic damage and is stronger than the rapier. A hit also forces the target to charge its nearest ally, or make a melee basic attack if it’s already close. This compelled attack is a free action, so it doesn’t eat into the PC’s turn. However, if the compelled attack hits, the coure gets to use Spark of Strife against the ally that was hit by it as a free action as well! A series of lucky rolls is going to rapidly turn the party’s well-tuned battle formation into a Three Stooges skit.

Sample Encounters and Final Impressions

The sample encounter here is level 10: 3 bladesingers, an eladrin twilight incanter from the first MM, and a will-o’-wisp which I guess might be the incanter’s familiar.

I love how the different eladrin celestial types from 3e became a bizarre system of nobility ranks with a lot of that good faerie flavor. As one rises in rank, one becomes less tied to the mortal world.

subscribe via RSS