Posts

-

Let's Read the 4e Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Nibenay

Nibenay, in his true half-draconic form, lounging on his throne. The Lore

Yes, he named his city after himself.

Nibenay seems to be a very academically-minded Sorcerer-King, which is evident in how his transformation seems to be the furthest along among the living ones, but he’s also kinda lazy. For about two thousand years now, he’s been holed up in his palace-temple complex of Naggaramakam enjoying a life of luxury and study while his priesthood took care of all those boring “running the kingdom” tasks.

His priesthood are also his templars, which are all women and all his wives. So this might explain why Dregoth outpaced him 1700 years ago - Nibenay still has his vices.

Nibebay’s highest ranking templars are known as the High Consorts. There are five of them, each in charge of one of the city-state’s temples. The Shadow King’s inner circle is composed of these five, plus his personal arcane assistants, his half-monster son Dhojakt, and a group of elite goliath warriors. Only they can enter Naggaramakam and interact directly with their king. And only they know what Nibenay’s true draconic form looks like - he disguises himself as a human in his rare public appearances.

Things might have continued this way forever if it wasn’t for Kalak’s assassination and the liberation of Tyr. This kind of lit a fire under Nibenay, and he decided to end his isolation and take a more active hand in the ruling of his domain. This has nearly all Nibenese nobles and a large number of lower-ranking templars in a panic because they’ve been up to a lot of self-enriching shenanigans that they were sure their king would never notice or care about. There’s a lot of unpleasant purges in the city’s immediate future.

Still, Nibenay hasn’t completely abandoned his research. He seems to be particularly interested in Athas’ distant past, and is rumored to be looking for a way to “bring about a new Age”. That probably involves some sort of large-scale environmental engineering, though it’s unlikely to be beneficial to the inhabitants.

The Numbers

We get three different stat blocks here, which we’ll see in order of level.

Shadow Bride

This is one of Nibenay’s lower-ranking templars. The city’s nobles tend to look down on them and use them as pawns in their own schemes - the name “Shadow Bride” is something of an insult. The brides resent them for this, and do whatever dirty deeds they need in order to claw some wealth and influence for themselves and climb the ranks of their organization.

This Shadow Bride is a Level 13 Soldier with 130 HP and Speed 6. She fights with an Obsidian Short Sword in melee, and with Shadow Bolts at range that do light cold+necrotic damage. She can inflict the Curse of the Shadow King an adjacent enemy with a minor action. This marks the enemy until the end of the encounter and makes it grant combat advantage for a turn.

Marked enemies within 6 squares who decide to ignore the mark can be targeted with Nibenay’s Retribution as an interrupt - the bride teleports to a square adjacent to the enemy and makes a very accurate attack vs. their Fortitude, dealing fire+necrotic damage on a hit.

In her own turns the bride can also Demand Penitence (recharge 5+), targetting up to two marked enemies in a Close Burst 5, dealing psychic damage, pulling them 4 squares, and knocking them prone.

Yup, this is a Soldier Warlock. Not a combination you see every day. The “eldritch blast” equivalent here is distinctly secondary. She wants to bring enemies into melee range and keep them there.

High Consort

One of the five highest ranked priestess-wives of Nibenay, part of his inner circle. Just like the city’s nobles, they jockey for position amongst themselves, constantly engaging in backstabbing and intrigue, though they are loyal to their hubby and will fight at his side against meddling PCs who manage to get that far. They will also fight to the end to protect their own temples. In any other situation, they run away when the fight turns against them.

High Consorts are Level 27 Artillery with 192 HP, Speed 6 and Low-Light Vision. They fight with Obsidian Spears in melee and with Shadow Blasts at range 20. These deal cold+necrotic damage.

Their special spell is Cage of Shadows (ranged 10), which deals heavy force damage and immobilizes (save ends). It recharges when they’re bloodied. They can also practice Arcane Defiling whenever they miss with this power or with a Shadow Blast while allies are present within 2 squares of them. This is a free action that inflicts 10 necrotic damage on each such ally, and lets the consort reroll the attack.

If they get surrounded, consorts can use Nibenay’s Gift (recharge 5+) as a minor action, dealing 15 cold+necrotic damage to each adjacent enemy, teleporting 6 squares, and gaining concealment for a turn.

Nibenay, Sorcerer-King

Nibenay in his true form is a Large Natural Humanoid, and a Level 29 Elite Controller with 532 HP. He has ground and teleport speeds of 6 and Darkvision.

His Sorcerer King’s Guile is going to ruin the day of many a PC fighter, as it makes him not provoke opportunity attacks from making ranged and area attacks.

In melee, he fights with Reach 2 Dragon’s Talons, which damage and restrain (save ends). At range, he uses the classic Ego Whip (range 10), which deals psychic damage and dazes (save ends). Yes, it’s at-will, and Ego Storm lets him use it twice in the same action.

Less often, he can use Defiling Burst (recharge 5+), which automatically deals 15 necrotic damage to each adjacent enemy and lets Nibenay attack an Area Burst 2 within 10 to deal necrotic damage.

The text is a bit strange here, as it says Nibenay gains +1 to the burst’s attack roll for each enemy damaged by it. I guess you roll once, count the hits, add the bonus, and keep repeating the last two steps until he either runs out of targets or misses someone.

As a minor action he can creaze a Zone of Shadows that lasts for a turn and blocks line of sight for everyone except himself. Enemies inside are blinded. The power recharges when the zone vanishes.

His version of Arcane Defiling triggers when he hits and deals damage with either of his basic attacks. It inflicts 10 necrotic damage on each enemy within 2 squares and weakens the target of the triggering attack for a turn. It’s a free action, not a reaction or interrupt, so this happens every single time he hits with Dragon Talon or Ego Whip.

Nibenay’s Demand is his anti-stunlock power, a reaction that lets him inflict 10 necrotic damage on an enemy within 5 squares and roll a save whenever he’s subject to an effect a save can end.

Encounters and Final Impressions

Nibenay being an Elite instead of a Solo is not necessarily a sign that he’s weak, but that the final fight against him will be a crowded affair. Any surviving high consorts will surely be here, as will any other epic level assistants and guards the GM wants to add to make the battle a worthy challenge.

Unlike Andropinis, Nibenay doesn’t have powers that boost or benefit from his allies, but at least he doesn’t get in their way either - his area attack is selective. The High Consorts, however, are likely to step on each others’ toes because their version of Arcane Defiling targets allies instead of enemies.

-

Let's Read the 4e Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Mearedes

Mearedes in her jungle home. The Lore

Mearedes is a goliath druid, the self-appointed Sentinel of Shault. Shault, in turn, is a hidden island paradise in the Sea of Silt, one of the greenest areas remaining in the Tyr Region, largely thanks to the efforts of Mearedes and her disciples.

Those disciples are the giants Shakka and Shola, and the dwarf Hippolexes. They, their master, and a few volunteers from the local stone and beast giant communities intercept any strangers making landfall on Shault, and demand they subject themselves to a ritual that prevents them from ever speaking about the island to others. Those who refuse are killed. As you might imagine, very few people ever return from Shault, and those who do aren’t saying anything about it.

Though Mearedes has an age-lined face, she’s still as spry as a young goliath, and has received the respectful title of “Little Grandmother” from the local giants. Those who help her and her friends fight off threats to Shault will find her to be a stalwart ally.

The Numbers

Mearedes, as mentioned, is a Goliath. She’s also a Level 18 Controller with 176 HP, Speed 6, and a lot of Classic Druid Powers, which might look very exotic to typical Athasian characters.

She fights in melee with a Thorny Staff that damages and slows for a turn; and at range with Flame Seeds that deal fire damage, and inflict 5 fire damage on any enemy that enters one of the squares adjacent to the target or starts their turn there before the end of her next turn. This means the target can take this additional damage if they try to move.

And then there’s the expected Lashing Vines (recharge 6+), a fireball-sized area attack that damages and then creates a zone of hazardous difficult terrain that lasts for the rest of the encounter. It damages and slows those caught inside. Yes, this is a recharge power, so the battlemap will become rougher and rougher as time goes on.

As a minor action, Mearedes can assume the Form of the Ghost Panther for a turn and shift 3 squares. In this form, she cannot attack but gains +4 Speed, insubstantial, and phasing. She can end this as a free action or sustain it for another turn as a minor action. And she also has the Goliath Stone’s Endurance encounter power, which lets her gain Resistance 10 to all damage for a turn.

Encounters and Final Impressions

Mearedes will almost always be accompanied by her three apprentices (whose stats are left as an exercise for the reader) and by as many stone and beast giants you need to make the fight interesting. She’s also clearly meant to be more of an ally than an enemy here, so she or some of her apprentices could also tag along with the group for a short while.

-

Let's Read the 4e Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Maetan of House Lubar

Maetan Lubar, posing for the cover of a business magazine. The Lore

Maetan is the current head of House Lubar, one of Urik’s wealthiest noble houses. He’s been prepared for leadership since childhood, though his time came much sooner than expected due to the untimely death of his parents.

The house makes its fortunes through commerce and through the ownership of many profitable fields outside of Urik’s walls. The work on those is performed by slaves, and their administration by junior house members. Senior leadership like Maetan has loftier concerns.

Maetan, for example, is busy petitioning Hamanu for the opportunity to lead a large army against the recently freed city of Tyr, as he has a story of success against Urik’s smaller enemies and wishes to attain new heights of glory and favor with the sorcerer-king.

This probably relates to the 2e Prism Pentad adventures, which saw the PCs take part in a battle against Urik’s forces. If this happens in your 4e campaign, Maetan will likely be at the head of those forces.

The Numbers

Maetan Lubar is a human, and a Level 16 Elite Controller with 302 HP. He fights using a combination of the fencing skills and psychic powers taught to him from a tender age.

The fencing is distinctly second fiddle here: just a basic Longsword attack that does level-appropriate damage with no riders. Maetan wants to stay a bit outside of melee range and use his many psychic abilities instead. He’s a telepath, so all of his powers target Will.

Serpent’s Kiss is a range 20 basic attack that targets up to 2 creatures, deals psychic damage and makes the target grant combat advantage for a turn. Insidious Worm is an at-will range 10 attack that can only be used against targets granting him combat advantage; it deals psychic damage and forces the target to make a melee basic attack against another target of Maetan’s choice. His usual routine would involve alternating these two.

Coils of Lubar is an area 1 within 10 attack that deals psychic damage and restrains (save ends). It deals 10 psychic damage as an aftereffect of the save. It recharges when he uses Psionic Augment, a power that triggers when Maetan hits with one of his two ranged at-wills and further boosts their damage. And this, in turn, recharges when he’s first bloodied.

His two final powers are Psionic Intrusion, a minor action ranged attack that dominates on a hit (save ends). This recharges when he’s first bloodied. And the Mind Fog encounter power, which triggers when he’s hit by a melee attack, affects a Close Burst 3, deals psychic damage on a hit, and forces the targets to treat him as invisible (save ends).

Encounters and Final Impressions

I guess this might be a typical example of an evil noble type. The book says Maetan will always be accompanied by a sizable honor guard, and in a fight he will try to use his powers to make things easier for those guards (all of them are selective, so he has no risk of hitting his allies). It also says that despite all of his psionic might, Maetan is still very proud and overconfident of his sword skills, so he might end up letting a PC get too close to him because of this.

-

Let's Read the 4e Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Lalali-Puy

Lalali-Puy in full regalia proudly standing in front of a vista of her kingdom. The Lore

Lalali-Puy is the Sorcerer-Queen of Gulg, which is possibly the greenest city-state in Athas. Out of all the Sorcerer-Kings, she’s also the most personally beloved by her subjects, who call her Oba or Forest Goddess.

She uses her magic to bring rain to Gulg, and to protect it from threats both external and internal. She also owns everything in Gulg, and is responsible for seeing to its even distribution among the dagadas (communities) in which its people live. If you’re a citizen of Gulg, everything you wear and eat, all the livestock you tend and the land it grazes on, all belongs to Oba, who graciously allows you to use it.

Of course, being a Sorcerer-Queen, Lalali-Puy has further dark secrets unknown to common citizens. The description of her capabilities above might read as “epic druid” to someone familiar with standard D&D, but that’s a lie. The reason she has so much power over her kingdom is because she keeps its primal spirits enslaved through arcane magic. And the spirits hate her for it. Given the smallest opportunity, they’d devastate Gulg’s dagadas in revenge.

Despite her villainy, Lalali-Puy is described as the most accomplished ritualist on Athas. Many of the arcane and primal rituals on her extensive library are unknown to even the other Sorcerer-Kings. PCs might find themselves having to ally with her in exchange for a specific ritual… or plotting a heist to steal it from her vaults.

The Numbers

We’ll take a look at some of Lalali-Puy’s servants here, and then at the Sorcerer Queen herself.

Nganga

This is one of Lalali-Puy’s templars, known as ngangas (witch doctors). When a citizen is selected for nganga training, they’re completely removed and isolated from society. From that point on, they only appear in public wearing scary demonic masks enchanted with fear powers.

The nganga we have here is clearly some sort of human warlock pacted to their Queen. They’re Level 11 Artillery with 90 HP and Speed 6. They fight in melee by bonking people with a spirit rattle that also serves as their implement. Their basic ranged attack is a Ghost Lance (ranged 20 vs. Fortitude) that deals necrotic damage. They can also use Spectral Jaws (Range 12 vs. AC) that deal force damage and immobilize (save ends).

The fear enchantment on the Devil Mask serves as a good keep-away power: Close Blast 3 vs. Will, deals psychic damage and pushes 3 squares. At the start of the target’s subsequent turns, the nganga can choose to push them 3 squares (save ends).

Finally, they can curse someone with a minor action with Curse of the Oba. The curse lasts until the end of the encounter, and they can keep cursing multiple people. They also really want to do that, because when the nganga deals damage to someone other than the cursed victim, the victim takes the same amount of damage. If the PCs aren’t quick to deal with the nganga, they’ll soon find their whole party being “focus-fired” at once.

Judaga

Judagas are the most elite warriors in Gulg. Like ngangas, they’re mostly isolated from society, though instead of masks they wear special enchanted leopard pelts preserved from the Green Age. Lalali-Puy has a honor guard of judagas with her at all times, and they can also be seen moving among the populace when she or the ngangas feel physical threats entering Gulg.

The example judaga here is a human, and a Level 25 Skirmisher with 231 HP. Their speed is the usual 6, but they also have Forest Walk and a +2 to saves against Charm and Fear effects.

Judagas fight with scimitars that do level-appropriate damage, and their Leopard’s Fury maneuver lets them shift 6 squares and perform a special attack at any point along the movement. This does a bit less damage than the basic strike but also inflicts 15 ongoing damage (save ends) and pushes 2 squares.

Lastly, if the judaga happens to be within 6 squares of Lalali-Puy herself (meaning they’re acting as a bodyguard) they can shift as a minor action.

The book explicitly calls judagas out as willing to perform a coup-de-grace on a downed PC in the middle of a fight, which makes them a lot more dangerous than their short list of abilities indicates.

Lalali-Puy, Sorcerer-Queen

The Oba herself is a human, and a Level 28 Solo Controller with 1032 HP and the Leader tag. She has a ground speed of 6 and a teleport speed of 3.

Lalali-Puy is surrounded by Ravenous Ghosts (aura 5) that give a damage boost to the melee attacks of any allies within the aura. Her Oba’s Ambition makes her regain one of her 2 solo action points whenever an enemy cursed by her drops to 0 HP.

As that description indicates, Lalali-Puy fights like a warlock. In a way, she’s a “role model” for an epic-level warlock - someone who has long surpassed whatever entity taught her magic in the first place, and who now makes pacts with others to teach them magic in exchange for service.

Let’s begin with the curse-related powers, because those are the core of her tactics. She can use Oba’s Curse once per turn as a minor action. This is exactly the same curse the ngangas can use, the one that mirrors melee or ranged damage inflicted on other enemies to the cursed victims. However, it’s (save ends) instead of lasting the whole encounter, because Lalali-Puy’s attacks are much stronger. Still, a string of bad save rolls could still have her “focusing down” the whole party a once.

Oba’s Vengeance makes that a scenario a certainty when the PCs manage to bloody her: this is a Close Burst 15 attack that affects enemies, deals necrotic+psychic damage, and stuns for a turn on a hit. It also curses every target as an effect (save ends).

Oba’s Blessing is a free action power that lets Lalali-Puy remove her curse from a victim to end an effect on her or on an ally within 20 squares, so here’s her stunlock protection.

Keep that damage mirroring effect in mind as we look at her “normal” attacks. All of them have additional things they do to curse victims.

Repelling Touch is the melee basic attack. It deals force damage, pushes the target 5 squares, and then pushes all other enemies cursed by her 2 squares as an effect. Spirit Maw is the ranged basic attack. It deals force damage, slides 4 squares, and slides every other cursed enemy 2 squares as an effect.

Spirit Gale is a fireball-like attack (Area Burst 2 within 15). It targets Will, deals necrotic+psychic damage, and immobilizes (save ends). This downgrades to “half damage and slowed for a turn” on a hit, but as an effect, it lets her slow one cursed enemy she can see (save ends). The first failed save from that enemy makes them stunned (save ends).

Her one power without any curse bonuses is Oba’s Punishment a reaction that triggers when she’s hit by an attack from an enemy within 15 squares. It’s a counterattack that deals psychic damage and teleports the target 10 squares on a hit. Since this is written as a Close Burst, it doesn’t benefit from damage mirroring, but it will still trigger pretty often.

Encounters and Final Impressions

I love Lalali-Puy’s mechanics. If the PCs end up fighting her, she will have an honor guard of judagas with her to use as distractions, all of which probably benefit from Ravenous Ghosts. And then she’ll curse as many people as she can and focus her single-target attacks on the weakest of them.

-

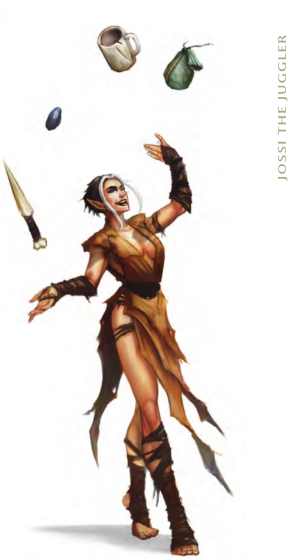

Let's Read the 4e Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Jossi the Juggler

Jossi the Juggler, juggling The Lore

Jossi gets a mention in the description of the city of Tyr in the Campaign Setting book, and a full writeup here. She’s a member of Tyr’s Eyes, which was originally a group of beggars, street performers and thieves who banded together for mutual support. Nowadays they also act as a kind of freelance spy agency, keeping an eye on what goes on in the city both to improve their own chances of survival and to sell the juiciest gossip to whoever has the money to pay for it.

Jossi is known as a street performer, doing a pretty impressive routine on the markets of Tyr. She supplements her income with theft and information broketing. I think both books’ emphasis on her might mean they intend Jossi to be the PC’s first point of contact with Tyr’s Eyes during your typical campaign.

The Numbers

Jossi is an elf, though her speed is only 6 and they forgot to add her low-light vision. After so many sorcerer-kings, it’s interesting to find a plain old Level 4 Skirmisher with 55 HP in the Personages of Athas section.

She fights with the same Daggers she uses in her juggling act, and her Juggling Slash technique lets her target Reflex instead of AC, deal the same damage as a basic attack, slide the target 2 squares, and shift 2 squares. This is at-will, making her very annoying to fight. On any turn where Jossi shifts as a move action, she also gains a bit of bonus damage courtesy of her Fancy Footwork.

As soon as she realizes the odds are against her, Jossi will try to escape. Distracting Toss helps with this: when someone makes a melee attack against her, the can shift her speed as a reaction to reach any square on the map that has any amount of cover or concealment, and then make a Stealth test with a +5 bonus (total +16) to become hidden.

Encounters and Final Impressions

Mildly interesting, I guess. Jossi is clearly more on the “possible ally” than on the “enemy” side of the balance, so unless the PCs go out of their way to be assholes or to antagonize Tyr’s Eyes, they won’t be fighting her. If that ends up happening, though, Jossi will not be alone. You should assemble a team of the many “low-Heroic street scum” stat blocks available here and in other books to act as the fellow Eyes members who come to her aid.

It could be interesting to have Jossi as an active ally in one or more fights, using these stats. Juggling Slash has hilarious synergy with what PC rogues can do, and Distracting Toss is a good way to quickly leave the fight in case her HP starts to run low.

subscribe via RSS