Posts

-

Let's Read the 4e Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Gaj

A gaj perched on a desert rock. Copyright 2010 Wizards of the Coast. This post is part of a series! Click here to see the rest.

The book opens this entry by that the wastelands of Athas “sometimes spawn monsters so terrible not even the merciful can permit them to live”. Cheery.

The Lore

The illustration makes me think a gaj is what you get when you mix a mind flayer with a beetle. These aberrations have human-level intelligence, strong telepathic powers, and a taste for the flesh and fear of sapient creatures. They’re too anti-social to practice infiltration like mind flayers sometimes do, but there’s still a lot about them that’s familiar.

Gaj dwell in extensive burrow networks that technically form a community, but they rarely interact with each other. They’ll band together to defend their home, but they mostly hunt alone or in mated pairs. They attack their prey with their claws and mandibles, and with invasive telepathy focused through their feathery antennae. Once a gaj has a firm grip on a victim, the touch of those antennae will rapidly disassemble the creature’s mind and use it to fuel further psychic assault.

Certain specimens mutate to assume a sort of leadership role in a gaj community. Their powers specialize on inflicting pain, and they take upon themselves the job of keeping victims captive in the burrow as dominated slaves and/or reserve rations for lean times. These Pain Tyrants are one of the few things that can get a whole burrow together for a bigger hunt or a raid against a settlement.

In really lean times, when gaj cannot find new victims and have already devoured all of their captives, they’ll turn on each other - even their own mates.

Ironically, just as gaj like to hunt other sapients, so are they hunted in return. They’re very popular in the arena, so those ubuquitous slavers often mount expeditions to find and capture them.

The Numbers

Gaj are Medium Aberrant Magical Beasts with a ground speed of 6, a burrow speed of 3, Darkvision, and Tremorsense 5. Their signature trait is Warding Shell, which gives them +2 to defenses against any creature marking them.

All of the stat blocks here are Chaotic Evil.

Gaj Mindhunter

This is the typical specimen, so named to distinguish it from the Pain Tyrant. Mindhunters are Level 8 Elite Controllers with 172 HP. Their basic attack is a bite with their Mandibles, which grab on a hit. Once the mindhunter has a victim in its jaws, it can only use this attack against it, and not against others.

Its Invasive Presence has no such restrictions. It’s targets one or two creatures within Range 10, deals psychic damage on a hit, and pushes 1 square. There’s also Mind Wrench (recharge 5+), which targets a creature within a Close Burst 3 and dominates on a hit (save ends). Each time the target fails the save, the mindhunter’s grabbed victim takes 2d6 psychic damage.

As a minor action, once per round, the mindhunter can use its Feathery Probe on the grabbed victim. On a hit this deals light psychic damage, 5 ongoing psychic damage, and dazes (save ends). If the target is already taking ongoing psychic damage, that damage increases by 5. Yes, repeated hits with this attack will result in more and more ongoing damage.

All of this paints us a picture of the mindhunter’s preferred tactics: choose a victim to bite and grab, get away from the PCs, and keep using Invasive Presence and Mind Wrench to keep them busy while they nom on the victim with Feathery Probe.

Gaj Pain Tyrant

Pain Tyrants are considerably stronger than mindhunters, being Level 13 Elite Artillery with the Leader tag and 200 HP. Its Mandibles have no special effects other than damage. Its ranged basic attack is a Mind Shriek with range 20, that targets 1-2 creatures, and on a hit deals psychic damage and dazes for a turn.

Less often they can use Agonizing Insight, an Area Burst 2 Within 20 with a lot of complicated effects. This weaponized anxiety attack inflicts 20 psychic damage on a hit (save ends). Whenever the target takes this ongoing damage, each of its allies within 3 squares also takes 5 psychic damage. So, if it hits 3 PCs, in the next round each of them is going to take a total of 30 psychic damage if they stay together: 20 from the main effect, 10 from splash damage. It recharges when the tyrant scores a critical hit with Phrenic Probe (see below).

As an effect the attack also makes each enemy inside the burst grant combat advantage for a turn even if they weren’t hit by the main attack. It also lets allies in the burst use a free action to either shift 1 square or move half their speed.

Against a dazed target, the Pain Tyrant can use Phrenic Probe as a 1/round minor action. This is a version of the mindhunter’s Feathery Probe that has range 20! Finally, Vicious Goad lets an ally within 20 squares move its speed and make a basic attack against an enemy of the tyrant’s choice as a free action. The ally is then dazed for a turn.

Encounters and Final Impressions

Looks like the most common gaj encounter in the wilderness is a pair of mindhunters. A Pain Tyrant leading a larger group is also possible, but in this case I’d recommend making the accompanying mindhunters into regulars of a slightly lower level than their boss. Enslaved humanoids can round out the group. And you can also find mindhunters being used as arena fighters.

These seem to be very tricky to fight.

-

Let's Read the Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Floating Mantle

An red floating mantle. Copyright 2010 Wizards of the Coast. This post is part of a series! Click here to see the rest.

The Lore

The Silt Sea makes up the eastern border of the known regions of Athas. No one knows what’s on the other side of it, and they have only the barest idea of what’s under the dust. Sometimes, weird creatures will drift in from those far and deep regions. One of these weirdoes is the floating mantle.

Floating mantles are giant flying jellyfish, though no one in Athas calls them that because they don’t know what a fish is. Despite their strong psionic powers, their flight is entirely mundane. Their bodies secrete a lighter than air gas into internal cavities to keep them aloft, and they expel small quantities of this gas to propel themselves.

These creatures live in small groups called colonies, which are psychically linked to form a collective consciousness. They have some fairly obvious sexual dimorphism: males are a pale red in color, while females are a pale yellow. Both grow much more vivid in coloration when they feel agitated or threatened.

During their reproductive cycle, the female will carry a large litter of “polyps” to term. This causes her to become larger, bluish in color and much more irritable, as the pregnancy is highly uncomfortable for her. When in this state, she’s known as a “bluesting”. When threatened, a bluesting might prematurely release some of its polyps, which can fight ferociously but don’t last long. Even when they’re properly birthed at the right time, polyps are still fragile and only a small fraction of them will grow up to join the colony.

The book describes floating mantles as “quiet and inoffensive”, which I guess means they only attack sapients if they feel threatened, or to defend their young. They probably feed on small animals, and mainly hunt on the Silt Sea. When they do fight, they use the same natural weapons they use for hunting: sting-covered tendrils that deliver a paralytic poison, and the ability to drain the life force of a helpless victims.

When hurt, a floating mantle emits a psychic scream that stuns attackers and warns their fellows of danger. Finally, the gas that they use is probably hydrogen, because it gives them an unfortunate tendency to explode when exposed to fire or electricity.

The Numbers

Floating Mantles are Aberrant Magical Beasts with the Blind tag, which makes them immune to blinding effects and gaze attacks. They perceive their surroundings with Blindsight 20. Mantles have a flight speed of 6, with an altitude limit of 3 and the ability to hover.

Adult mantles are vulnerable 10 to fire and lightning. Polyps have too little stored hydrogen for this.

Flying mantles are also immune to the effects of their Psychic Scream powers, whether used by themselves or by another mantle.

Floating Mantle

This typical specimen is Small in size, and a Level 13 Controller with 126 HP. Its basic attack is a Tentacle Rake (melee 2 vs. reflex) that deals poison damage and slows for a turn. If they have combat advantage against a target, they can use Life Leech (melee 2 vs. Fortitude) as a minor action. This deals poison damage, dazes and immobilizes (save ends both) and gives 10 temporary HP to the mantle. Of course, a target who’s hit by this once becomes susceptible to it until they save against that daze, since dazed characters grant CA.

Also as a minor action, the mantle can squeeze out a Jet to shift its speed.

When the mantle is first bloodied, a lot of stuff happens. First, Jet recharges. Then it lets out a Psychic Scream! The scream is a free action attack vs. Will in a Close Burst 2. On a hit, it deals psychic damage, and makes it so the affected targets take 10 psychic damage whenever they make an attack against the creature (save ends). As an effect, the floating mantle becomes invisible until the end of its next turn.

If the mantle is reduced to 0 HP by fire or lightning, it suddenly explodes! This is another Close Burst 2, vs. Reflex this time, dealing high fire damage and pushing targets 1d4 squares. On a miss, it does half damage. This is probably the only variable push I ever saw.

Floating Mantle Bluesting

Bluestings grow to Medium size. They’re Level 15 Artillery with 111 HP, and a greater blindsight range of 25.

Their Tentacle Rake Attack has reach 3 and does more damage than the common mantle’s, and they also gain the ability to fling their tiny stingers at distant targets. This Flinging Nettles attack targets Fortitude and deals poison damage out to range 20.

If enemies manage to get close, the bluesting can let out a Toxic Burst, which targets creatures in a Close Burst 1 and deals poison damage on a hit. If the bluesting has less than four accompanying polyps, one appears in an adjacent square, acting right after the bluesting in initiative order.

They have the same Jet ability as the common specimen, and can also perform a Sudden Birth (recharge 4+) as a minor when pressed. This is more or less the same as the secondary effect of the Toxic Burst above: it puts a new polyp in play within 3 squares if there are less than four accompanying the bluesting.

Psychic Scream and Sudden Explosion work the same as in the common specimen, but do more damage since bluestings are higher level.

Floating Mantle Polyp

These Tiny youngsters can either be pre-placed in an encounter, or be produced by bluestings (in which case they’re not worth XP). A previously-placed polyp is one that reached term and was birthed normally, and adults will fiercely defend it. One produced during combat is considered premature and will die a few minutes after the fighting stops. Adults are less attached to those. In either case it’s not yet hooked up to the hive mind and it’s recklessly hangry.

Polyps are Level 15 Minion Brutes. Their Tentacle Rakes do poison damage, and when they die they let loose a Psychic Scream in a close burst 2, which deals psychic damage and dazes for a turn on a hit.

Encounters and Final Impressions

These are likely the most peaceful and sympathetic aberrant creatures you’re likely to find anywhere. They’ll most likely be found just chilling and minding their business, and will only become dangerous if the PCs strike the first blow. The capybaras of the Far Realm.

Their lore is both disturbingly biological and a breath of fresh air. The first part is obvious (poor premature polyps!), and the second one is because here we have an example of powerful Athasian wildlife that isn’t so mindlessly aggressive it thinks armed adventurers are a good meal.

Standard flying mantles need to either appear in pairs or have some other opportunistic flanking buddy that will help them get their initial combat advantage on a target. Other than that all of them have some interesting ways to punish PCs that do too well against them.

-

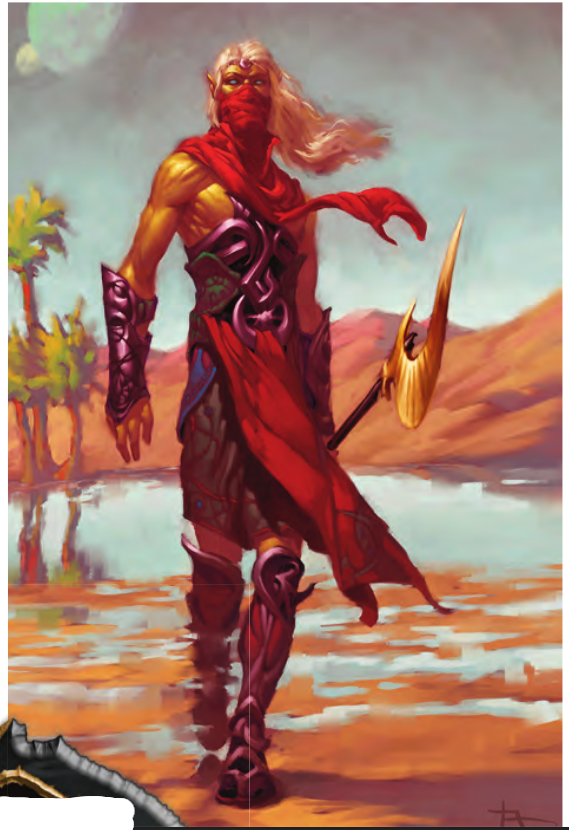

Let's Read the Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Elf

An elf running through the desert. Copyright 2010 Wizards of the Coast. This post is part of a series! Click here to see the rest.

The Lore

Athasian elves are tall and long-legged, and their culture is almost entirely nomadic. Elven communities roam the deserts of Athas accompanied by swift beasts of burden and war, but none of those are mounts. An elf will only accept being carried by a beast if they’re too sick or wounded to stand. Otherwise, they prefer to run. And they’re very good at it.

Unlike some of the other nomads we saw so far, such as brohgs, elves have frequent interactions with Athasian settled peoples and city states. Their overall reputation is not very good. They’re known as itinerant traders who bring a lot of cool stuff to sell in the Elven Markets many towns have, but they’re also known as swindlers, thieves, raiders, and occasionally murderers. The cool stuff they sell you was probably stolen from someone else, according to rumor.

This sort of reputation has a number of unplasant parallels with real-world prejudices, so I find it off-putting that the book spends a lot of effort trying to convince me it’s true. Even the PCs have “desert raider” and “market thief” as their new custom background options.

I’d prefer to portray elves as having a lot of solidarity for each other and not a lot of sympathy for the outsiders who hate them so much. They drive hard bargains at the Market and skip town en masse if it looks like someone’s going to accuse one of them of a crime. The accusation is likely to be false most of the time, as I interpret it. Some individuals might resemble the negative stereotype, but then again that’s also true of city-dwellers, whose negative stereotype is “servant to a slaving despot” or “slaver”.

Elves who are found guilty of crimes in their own communities are cast out, and will often end up joining groups of actual raiders and bandits.

The Numbers

Despite their taller build elves remain Medium Fey Humanoids with a ground speed of 7. The stat blocks here don’t have low-light vision, though I think that’s still a feature of PC elves. They do all have Wild Step and Elven Accuracy, which work like their PC versions too.

The level range here is roughly comparable to that of standard elves from other books, so you can mix-and-match a bit. All of the stat blocks here are Unaligned.

Elf Peddler

A typical denizen of the Elven Markets. This could both represent a more or less honest trader who knows how to defend themselves, or a cutthroat who looks for particularly vulnerable customers to ambush after a sale. It’s a Level 2 Skirmisher with the Leader tag and 34 HP.

A typical peddler’s goal in a fight will be to live to fight another day, so they always hang around places with convenient escape routes and obstacles that might deter pursuers, such as twisty alleys or clustered stalls.

The peddler is armed with a bone longsword, which does standard damage for its level. It can use the Double Dealing maneuver at will: this lets it make a sword attack, shift half their speed, and then make another sword attack against a different target if they end the shift flanking that target.

As a minor action they can also use Peddler’s Command, which lets an ally within 20 squares move half their speed as a free action. If that ally is another elf, the move is instead a shift. This is useful to set up the flank for that second Double Dealing attack.

Elf Sniper

Another typical denizen of the markets, Snipers work security from shadowy corners and rooftop perches. If trouble starts, they help cover their allies’ retreat with their thrown weapons.

Snipers are Level 3 Minion Lurkers armed with Bone Daggers and a brace of 10 Chatkchas, which are three-pronged sharpened boomerangs. Both of these attacks deal a bit of extra damage if the sniper is hidden from the target when they start the attack.

As an at-will Move action, the sniper can use Elven Misdirection to move 2 squares and make a free Stealth check to become hidden if they end the movement with cover or concealment. This check has an automatic result of 25, which means they “take 15” on the roll.

In combat, they’ll try to pop out from cover, make a ranged attack, and hide again. If someone tries to get close to them they will run. Like the peddler, their goal in a “market fight” situation is to delay and distract pursuers enough for their allies to flee, and then flee themselves.

Elf Dune Strider

This nomadic warrior is used to running through the wastes. This stat block can represent a raider, or someone who’s just protecting their wandering band. It’s a Level 4 Skirmisher with 52 HP.

The Dune Strider can Move Like the Wind, gaining +5 to all defenses against opportunity attacks provoked by movement. They’re armed with a Bone Longsword that does extra damage on a charge, and a Obsidian Shortsword that’s slightly better for static attacks. The Rushing Dervish maneuver lets them move their Speed + 2 and make one attack with each sword against a different target during the movement. This recharges when they’re bloodied.

Striders acting as raiders will keep mobile and try to spread out their attacks in an attempt to intimidate their targets into giving up their possessions. They will flee if the fight turns against them. Their traits and abilities make it easy for them to bounce around the battlefield like pinballs, making charge attacks.

Elf Raid Leader

The sort of veteran commander you might find leading a larger raid against a settlement, either as revenge for mistreatment or as a plain old resource grab. It’s level 6 Artillery with the Leader tag.

The leader has a obsidian shortsword for emergencies, whose strikes let it shift 1 square on a hit. It will mostly fight with its Bone Bow, which is both more accurate and more damaging. It can fire Harrying Shots that do the same damage as a basic ranged attack, but also make the target grant combat advantage to adjacent allies of the leader for a turn.

Its leaderly action is a command to Focus on the Pain (minor action, recharge 6+) which deals 5 damage to an ally within 20 squares and allows that ally to immediately roll a save with a +2 bonus.

Raid leaders obviously lead from the back, providing ranged support to their skirmisher and lurker allies. It might be good to add a brute or soldier war beast to help protect them.

Encounters and Final Impressions

I’ve already mentioned my opinion about the elven stereotypes here: I don’t like them, and would probably change them a bit were I to run a campaign in this setting. They would be less true than depicted in the book, and depending on the tone I was going for might or might not be less prevalent in the setting.

The stat blocks are good, and can make for an extremely mobile encounter group when used together. As mentioned above, any brutes and soldiers who are part of an all-elven group will likely be trained war beasts instead of more elves.

-

Let's Read the Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Eladrin

An Eladrin Veiled Warrior stepping out of a mirage. Copyright 2010 Wizards of the Coast. This post is part of a series! Click here to see the rest.

The Lore

Physically, Athasian eladrin are very similar to those of the core setting, but the near-total loss of their home plane has done a number on their psychology and culture.

Defiling magic didn’t just destroy Athasian ecosystems - they also dissolved its Feywild. Now only a few rare pocket dimensions remain, scattered like oases through the wastes. The fate of the Lands Within the Wind is still tied to that of Athas, which means they’re slowly dying just like the world is.

Similarly, Athasian Eladrin are a traumatized and dying people. Most of the ones that remain live in remote castles and settlements in the desert or inside surviving pockets of Feywild, guarding the entrance to their realms with psychic illusions and only venturing out when they must.

The Numbers

Eladrin have the same common stats as always: they’re Medium Fey Humanoids with a Speed of 6, Low-light vision and a +5 on saves vs. charm effects. They retain their signature Fey Step power, which lets them teleport 5 squares as a move action once per encounter.

These stat blocks occupies what would be the lower range of eladrin power levels from the Monster Manuals and Monster Vault. There are no more epic-level ghaeles and bralanis in Athas… probably.

Eladrin Veiled Warriors

Veiled Warriors are spies and scouts that range far away from Eladrin settlements to gather information and locate resources, thought hey can also be found as part of their homes’ defense force. This is a great origin for PCs!

NPC Veiled Warriors are Level 5 Soldiers with 60 HP. They fight with Reach 2 Longspears that damage and mark for a turn on a hit. Once per encounter they can use a Veiling Dart (ranged 5 vs. Will) which deals psychic damage, blinds for a turn and slows (save ends).

Eladrin Mirage Adept

These are the psions responsible for hiding Eladrin settlements. They’re Level 7 Controllers with 80 HP and a focus on illusion powers.

Their basic melee attack is a Dagger that deals psychic damage and slows for a turn. They can attack at range with Deluding Whispers (ranged 10 vs. Will), a charm power that deals psychic damage, slides 3 squares and prevents the target from seeing creatures not adjacent to it for a turn.

Occasionally they’ll strike with the Phantom Foes power (recharge 6, area 2 within 20 vs. Will), which I guess projects the illusion that many additional foes are attacking the targets. This “psychic fireball” deals psychic damage and confuses (save ends). Confused characters roll a d20 whenever they’re about to make a melee or ranged attack and an ally is also in reach of that attack. On a 10 or higher, they attack the ally instead of the intended target.

Mirage adepts are very effective when combined with veiled warriors, because the warriors use reach weapons and so don’t need to be adjacent to a target blinded by Deluding Whispers in order to attack.

Eladrin Windwalker

Some eladrin indiscriminately blame all people of the natural world for the fate of their homeland, and feel such overwhelming hatred towards them that they offer themselves in ritual sacrifice. This causes their life essence to slowly leak into the Feywild and be replaced with the raw magic of that plane. This gives them great power for as long as their diminishing life lasts. They use their remaining time to go out into the world and slay every humanoid they see.

Windwalkers are Level 8 Lurkers with 69 HP. They fight with sabers and blowguns that ignore armor and target Reflex. Their damage is average, but Unseen Advantage lets the windwalker deal extra damage against targets that can’t see it, and slow them for a turn on any hit.

The Between the Winds trait lets a windwalker become invisible and gain phasing whenever it either spends a turn without attacking or uses its fey step. These conditions last for a turn or until the windwalker attacks. This does mean they can stay continuously invisible if they don’t attack.

Windwalkers will usually try to attack every other turn like most lurkers to benefit from Unseen Advantage, but the presence of an ally who can make them invisible or blind PCs (like a Mirage Adept) can let them strike every turn with bonus damage.

Eladrin Windwalker Mirage

Windwalkers in the final stages of the process are little more than ghosts. They become Level 8 Minion Lurkers with a ground speed of zero, a flight speed of 6 (hover, altitude limit 2), always-on phasing, and Resist 10 All. Despite appearances they are not undead, and are not especially vulnerable to radiant damage and anti-undead powers.

Their Wisp on the Wind trait gives them partial concealment vs. enemies that are 2 or 3 squares away, and total concealment against enemies 4 or more squares away. Their melee attack is a Razor Wind that does minion-tier damage. When they hit 0 HP, their Dispersing Essence attacks a Close Burst 3 and does the same damage as Razor Wind to those it hits.

The mirage’s damage resistance means you can only get it to that point by dealing 11 or more damage with a single attack - they’ll resist anything weaker. On the bright side, this means Dispersing Essence cannot provoke a chain reaction as it only deals 8 damage.

Mirages love large battle maps that let them invisibly fly past the party’s defenders and gang up on isolated squishies. PCs can counter this tactic by sticking together, but Dispersing Essence makes that decision a bit tougher than it would seem at first. Cruel GMs can make it even harder by including other monsters capable of area attacks in the encounter.

Encounters and Final Impressions

The Windwalker variants are evil, having succumbed to genocidal rage, but everyone else is unaligned. And they’re all super tragic.

I don’t think windwalkers would mix with other eladrin, though it’s easy enough to reskin a standard Mirage Adept as another windwalker variant if you want to mix them up. As noted above, this makes for a potent combination.

-

Let's Read the Dark Sun Creature Catalog: Dune Reaper

A dune reaper. This image is mirrored from the one in the book. Copyright 2010 Wizards of the Coast. This post is part of a series! Click here to see the rest.

The Lore

Like a lot of other Athasian fauna, dune reapers are predatory insectile/reptilian pack hunters. However, they lean a lot more towards the “insectile” side, and their origins are clearly unnatural even to contemporary inhabitants of Athas.

The book says they “came to existence through defiling magic”, though it doesn’t specify whether they were an artificially engineered species or whether some side effect of defiling brought them to the world. Their Aberrant origin kinda hints at the latter.

These creatures have a complex social structure. They organize into large familial groups known as prides, who build large hives from sand, rocks, and organic secretions near a water source that becomes the center of their territory. The pride then splits up into smaller packs, which roam that territory looking for food. A pack is composed of a large female “warrior”, accompanied by smaller male “drones” and “shrieks” who are her mates. The pride’s dominant female is known as its “matron”, and it’s her who makes decisions that affect the whole pack, like where to build the hive or when to seek new territory. A matron rules the pride until her death, which is usually in a duel with an up-and-coming warrior who challenges her for the position.

Dune reapers are a scourge on the local ecology. Their menu includes just about everything they can reach: humanoids, animals, plants, wagons, buildings… they even eat rocks to store in their gizzards and aid in the digestion of tougher food. A humanoid settlement in dune reaper territory is only safe if they can provide the creatures with an ample alternate source of food.

Dune reaper reproduction happens on an annual cycle, and they’re even more dangerous during mating season. The pride’s females need to lay their eggs inside the bodies of living creatures, you see. When the eggs hatch, the newborn reapers eat their host, and then set upon each other. Only the strongest hatchlings survive this process. After about two months they’re already as dangerous as a fully grown adult. At this time, they’re driven from their birth hive and must either join another pride or form a new one with other young reapers.

The Numbers

Dune Reapers are Aberrant Beasts with Darkvision. Their basic melee attack always uses their Arm Blades, which do standard damage for their level and might have other effects depending on the stat block.

Dune Reaper Drone

These relatively small males are Medium and make up the dune reaper worker caste. They build the hive and carry food back to it, but as Level 12 Skirmishers with 120 HP and Speed 8 they’re certainly strong enough to take part in the hunt as well.

Their basic arm blade attack also lets them shift 1 square on a hit. They can perform a Leaping Slash that lets them jump 4 squares without provoking opportunity attacks and use Arm Blade at the end of the movement. This recharges when they’re first bloodied.

If an enemy grants Combat Advantage to the drone, it can use a minor action to bite, dealing light physical damage on a hit. If an enemy makes a melee attack against the drone, it can Leap Away, jumping 4 squares without drawing OAs, as an immediate reaction.

Drones want to leap into melee at the start of the fight, and seek positions where their chosen target grants them CA. They’ll leap away when attacked and come back from an unexpected angle. When fighting drones, shoot them or surround them. Don’t let them surround you.

Dune Reaper Shriek

That’s not a role you usuall find among mundane insects. The book considers them specialized drones that can leap not just through the air, but through time and space. When they do this, they emit an ear-splitting scream that gives them their name. They’re Level 14 Lurkers with 106 HP and Speed 7.

Their arm blades are standard attacks with no riders, and are a lot more dangerous when used in conjunction with the shriek’s freaky powers. A Shrieking Reap lets them make two arm blade attacks against the same target. If one hits, it teleports the target 2 squares and inflicts 10 ongoing damage (save ends). If both hit, the teleport distance increases to 5, and the ongoing damage to 15. A Shrieking Warp removes the shriek from play until the start of its next turn, when it appears at a spot within 10 squares of its previous position and makes a Close Burst 2 attack that deals thunder damage and pushes 2 squares on a hit.

Shrieking Warp is an at-will ability, but it’s disabled for a turn when the shriek takes force damage because of its Forceful Silence trait. Shrieking Reap recharges whenever the creature uses Shrieking Warp. Our lurker loop here is Shrieking Reap -> Shrieking Warp -> Repeat.

The book reminds us that forced movement is always voluntary for the attacker, so shrieks arriving from a Warp will often choose to push all but one of the enemies they hit with the attack, to isolate it from its allies. Clever!

Dune Reaper Warrior

This Large female will lead a pack of drones and shrieks when hunting. She’s a Level 15 Brute with 180 HP, Speed 7, and the Leader tag.

She exudes an aura (3) of Inciting Pheromones that grants all dune reapers inside a +2 bonus to Will, and makes them immune to the Dazed condition. She also has the Unhindered trait we saw before, which lets her drag grabbed characters around when she moves.

Her arm blade is Reach 2 and extra-strong. She can perform a Leaping Slash similar to the drone’s, which also inflicts 10 ongoing damage if either attack hits.

Her triggered actions make her even more dangerous. Snapping Mandibles triggers when someone hits the warrior with a melee attack. As a reaction, she attacks their Fortitude and grabs them on a hit. Grabbed targets take 10 damage when they fail an escape attempt. Her Compelling Musk (recharge 5+) is triggered when she misses with an Arm Blade attack, and lets another dune reaper within 3 squares make a melee basic attack as an opportunity action. I’m not going to make a joke about that power name, it’s too easy.

Encounters and Final Impressions

Dune reaper packs number between 5 and 12 (!) individuals. Only one will be a warrior, though you could say the PCs found more than one pack together if you want there to be more of them.

Reapers are impossible to train, but sapient humanoids still capture them for use as arena beasts, and hunt them as a source of leather, organic armor plates, and blades.

These seem to me like yet another pack-based predator, the third or fourth we saw in this reading. I do like the ominous aberrant touches in both their lore and mechanics, though. The shriek in particular reminds me a lot of a Hound of Tindalos.

subscribe via RSS